4. 1 Introduction

A core aim of our research programme was the development of a participatory methodology that placed young people at the heart of our research journey. The Whitley Young Researchers (YR’s) of nine sometimes ten or twelve students, emerged mainly from Year 9s in John Madejski Academy (JMA) following the ‘home build’ project (see Chapter 3).

This chapter brings together the findings from a series of interactive research activities that were designed by the Young Researchers to open up conversations with primary and secondary schools students in South Reading. It also traces the journey taken by the Young Researchers through their exploration into the theme of ‘aspiration’ using four main methods2:

- Playing the ‘Aspiration Game’ – a snakes and ladders inspired game designed by the team.

- Peer-led survey with 38 young people.

- Photographic fieldwork around Whitley and the University’s Whiteknight’s Campus – their photographs as displayed throughout this report1.

- Community Panel (discussed in Chapter 7).

This chapter is divided into two sections: 4.2 Youth Aspirations and 4.3 Student Survey.

1This chapter presents the data from the aspiration game and youth survey. The Young Researchers could not be individually named due to data protection rules.

236 We hope to run an exhibition of their entire collection in Autumn 2018

4.2 Youth Aspirations: The Aspiration Game

Design and development of the ‘Aspiration Game’

In October 2017, the YRs devised a game based on snakes and ladders through which they could open honest conversations with peers about the things that hold them back and about the things that help them forwards. The team designed the board themselves with the help of Mr Allen and John Ord (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 The Aspiration Game designed by the JMA Young Researchers

- In November 2017 the YRs invited other JMA students from Years 7-10 to play the game.

- In March 2018, the game was played in Reading Girls’ School1 (RGS) with a team of nineteen Year 8 students.

- March 2018 children from Years 1-6 played the game in The Palmer Academy.

In total, around 70 young people were involved with playing the game from these three venues – all games were led and supervised by the YRs.

The game appeared to be a simple and effective way of getting people talking things through, and thinking about where improvements can be made2. It also helped students to express what they feel. As some students put it, the process gave them a voice.

Playing the aspiration game at JMA

About 30 JMA students from years 7, 8, 9 and 10 played the game. Participants sat around a metre-sized board based on the snakes and ladders game; snakes hindered and ladders helped aspiration. Extra symbols such as stars, or circles invited further reflections. The adult Whitley Researchers3 were on hand to help record the conversations and report back on the day. At game completion individual students completed a personal aspiration card.

JMA Student Aspiration

Everyone who filled in the aspiration cards (26 in total) laid out some aspirations, even though not all were clear about their future career objectives and thinking about aspirations did not come easily to all. Four respondents only mentioned very short-term goals to do with achieving present targets at school, and had nothing to say about their wider or longer-term goals. Outcomes included:

- The majority of students mentioned some kind of career, with most having thought of specific jobs already, and a couple even mapping out detailed career paths including getting work experience and/or certain qualifications to meet their goals.Possible careers ranged widely from fashion model, or performer, through to designer or diplomat, to the medical profession. It could be observed that many career ideas were not fixed. Students who mentioned a specific career were often inspired by someone they knew or admired.

- Besides aspirations to do with work, most people also (and sometimes exclusively) mentioned non-career related goals. The top non-career related goal was linked to relationships. Firstly, students hoped for happy families. Secondly, having plenty of money - especially for a nice house. In third place were aspirations related to the kind of person students wanted to be – being a better person, being able to help people and helping family at home were all mentioned.

- Girls were more likely to mention non-job-related aspirations than boys. Younger respondents were just as focused in their answers as older respondents.

- Three students were entirely dismissive about their future, even refusing to fill in the cards or engage with the questions in the game. Two of these did not want to interact at all except to say that they have “no idea about the future”. Three young people alienated from the current system are not many, although they still represent a good 10% of the sample, and a significant number of other students also expressed uncertainty or confusion about occupational aspirations.

In summary, the majority of young people had clear aspirations in spite of a significant level of uncertainty, and educational attainment played a prominent part in these. ‘Aspiration’ was not confined only to career related goals however. Good relationships were key and girls especially recognized this.

What holds students back and what helps them forwards

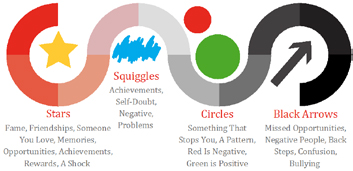

Information on what holds students back and what helps them forward was mainly drawn from conversations during the playing of the game, but also from whole group feedback at the end, and from comments posted on the comments board. Figure 4.2 shows some of the emotional responses JMA student’s discussed when they landed on a symbol and Figure 4.3 highlights some of the issues raised in the snakes and the ladders.

Figure 4.2 - Student’s responses to landing on symbols

Figure 4.3 Snakes and Ladders: what helps and hinders

Summary of key conclusions from JMA

Through discussion with JMA students it was possible to explore the theme of youth aspirations with a view to understanding how better to support students in their progress. Following the playing of the game the YRs drew out the following key issues and recommendations:

- Relationships are important. This is especially in the home (many homes are very busy, and multiple traumatic experiences were touched on). The influence of friendships turning sour is also huge. Bullying is a concern that needs to be better addressed.

- Young people are inspired/led by others. The positive influence of visitors, guest speakers and role models was emphasised. It would help expand horizons if new people were to come in to talk about their experiences, or if students could go out to see what other people do. Negative influences are also prevalent in the locality, which can pull students into unhelpful ways. Visiting speakers can also help to raise awareness of these dangers.

- Getting help at school. Students find it easier to ask for help from teachers they know and have taken an interest in them by asking questions in and out of classroom settings.

- Students want a voice. Although they look for guidance from role models, and although this could be helpful to them if they have positive influences, our participants need to be helped and inspired to find their own way and to work out their own steps into the future. There could be value in introducing a space in which constructive two-way conversations may be had, such as was provided in the context of this exercise.

- Students feel under pressure to get high grades. Current pressures are acutely discouraging to those who do not get high grades. Tailoring advice and direction in ways that are appropriate to the circumstances of each person is of more value than generalised pleas to ‘raise aspirations’.JMA students felt the pressures to get good grades were clearly alienating them from the whole schooling process when things were not working out. Indeed, many students expressed high levels of discouragement when they hit another setback.

How can these students be supported, and especially in the face of a severely testing social and emotional environment for many?

(There is considerable debate about the effectiveness of the link between aspiration and attainment – please see our full report presenting an outline discussion here from [email protected]).

- Life chances and family trauma. A significant number of students face a testing social and emotional environment, and this is known to negatively impact aspirations. Family trauma, such as missing family, crowded and unhappy households, eviction and illness were all mentioned by JMA students. Anxiety was an issue that came up repeatedly. Understanding and addressing these stress factors is important in order to reduce discouragement and allow aspirations to rise.

- Aspiration and community. One of the most notable findings from observing conversations around the aspiration game at JMA was the lack of discussion around ‘the community’. Many young people had very limited experience of what’s happening in their own communities, they rarely attended after school clubs or had relationships with anyone outside of the school and home.

Young people often feel isolated and disconnected to the wider world and this impacts on their understanding of future opportunities. Community issues outside of the school were only just touched on, despite the influence they are known to have on attainment, and we feel this is a significant gap that needs to be addressed. (Explored further in Chapter 7).

Issues for exploration include:

- The extent to which schools can provide a more tailored curriculum with enriching activities;

- How students who do not get high grades can be encouraged to take on a positive attitude towards learning and their life options;

- More information on barriers related to life in the wider community, including housing and family issues as well as relationships between people more broadly.

Playing the aspiration game at Reading Girls’ School

As part of Reading Girls’ School’s (RGS) Activities Day programme, nineteen Year 8 students were led in the aspiration game by the Whitley Researcher’s team. A whole group discussion was also facilitated about the concept of aspirations before the students each filled in cards about their aspirations and played the game.

RGS Student Aspirations

Out of 19 responses in total, 17 students mentioned an aspiration (mostly career related) and two did not. Out of the two that did not mention aspirations, both said that they had not decided on a career yet, the ‘yet’ implying an expectation that they expected to make a choice of career in time.

Regarding the sort of jobs that the students picked, there was a fairly even split between creative jobs (hair dresser, designer, performer etc.) and jobs such as teacher, lawyer or medic. There were just three non-career related aspirations, which included getting good exam grades, a character-related aspiration and job related travel.

Wanting a family (or not) and how to juggle family responsibilities came up, along with the importance of taking care of one’s parents when old and how you need your own children to do the same for you.

(RGS help and hinder factors are available in the full report from Sally Lloyd-Evans).

Summary of key conclusions from RGS

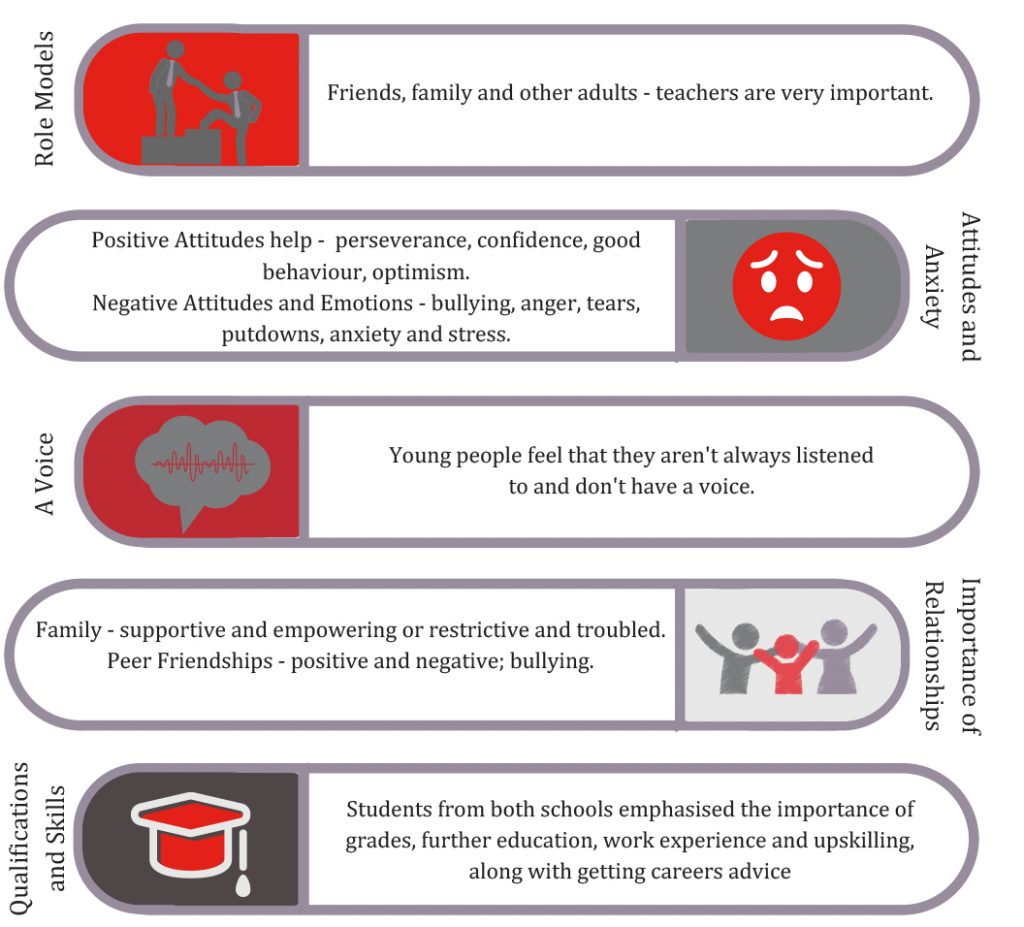

Despite some differences, there were a number of reoccurring themes common to both Reading Girls and JMA, shown in Figure 4.4

Figure 4.4 Findings from JMA and RGS

Playing the aspiration game at The Palmer Academy Primary School

“When you are very young you are full of big ideas, but as you grow up you lose them” (Young Whitley Researcher commenting on playing the game with The Palmer Academy)

The Young Researchers were invited to The Palmer Academy in March 2018 to play the aspiration game with members of the school council. This is made up of 22 children from years 1 to 6 who were each elected by their class mates to be their representatives4.

The event was led very effectively by the Young Whitley Researchers from JMA who explained the programme, asked children about their aspirations, ran the snakes and ladders game with them and also interviewed each child individually for a video presentation. Other members of the Whitley researchers helped to record the conversations during the event.

The Palmer Academy student aspirations

100% of the children said that they had aspirations. They were very forthcoming, random, changeable and enthusiastic! Nearly all of the child aspirations were job related. Just over half of these jobs were sports or performing arts related, and the others varied from policewoman and teacher through to scientist, doctor, vet, archaeologist and astronomer! A few covered several different options and one or two were more general (‘I want to be a leader’ for example).

The children enjoyed thinking up ideas for what the different symbols on the board could mean and came up with some very creative answers, sometimes telling whole complex stories around possible positive or negative scenarios. There were a few wide- shot answers to questions about things that help you forward (e.g. playgrounds, Christmas!) but on the whole the children were very aware of similar issues as the older students.

(The Palmer Academy help and hinder factors are available in the full report from Sally Lloyd-Evans)

Summary of key conclusions from The Palmer Academy

Attitudes were recognized as important, especially confidence, hard work, and seeing the big picture. Anxiety issues were already being mentioned as problematic.

Some incredibly discerning comments were made about the impact of small achievements or small failures, which subsequently encourage (or discourage) you from moving on to bigger things.

Children talked about examples that were taken directly from their own experiences: “Mum can’t earn money if it is snowing”, “we can’t go on holiday because of work”, “the family is threatened by the police” (a refugee family) as well as mental breakdown; sickness; “parents having other ideas to me...”

The Young Whitley Researchers remarked, following the experience of interacting with years 1-6, on how it is that “when you are very young you are full of big ideas, but as you grow up you lose them.” Perhaps ‘reality hits’ as they become more aware of the limits they face. It was clear that the older students had become more perceptive and discerning regarding the positive and negative impacts that other people were having on them.

The Aspiration Game: Key Findings

The key findings uncovered by the Young Researchers and their participants at RGS and The Palmer Academy revolve around six themes that we will discuss in turn:

1 The centrality of family and friendship networks:

- Family and friendship networks change everything, whether helping you forward or setting you back – weak relationships with the wider community and/or parent-school relationships can have a negative impact.

- “Fake friends” and bullying were sources of heartache; Young people do not feel that enough is being done about bullying. They loathe and are disturbed by injustice.

- It is important to have people who believe in you and who

have your best interests at heart. Not everyone gets this from family. Some young people who felt supported were inspired to “make [their supporters] proud”.

2 The desire young people have to find their own voice and place:

- Young people want two-way relationships with adults. They want a voice, and help in finding their voice and place-tailored guidance. Also opportunities to have a go at things.

- Understanding where other people are coming from is important: “Hearing how others think helps your own thinking.” “Sometimes you don’t realise what other people are dealing with.” Being understood/having someone to talk to is also important.

- Young people did not feel that their circumstances hold them back. This sense of “the future is up to us” is positive in terms of motivation and progressive action. But learning not to feel pressured by things that are beyond personal control is also important to wellbeing.

- Many young people do not have regular trips/experiences outside of Whitley. “We go from home to school and back home.” “I’m not going anywhere.” Involvement in out-of- school activities is low.

3 The high levels of anxiety faced by young people who are sometimes found to be in highly stressful family circumstances:

- Anxiety came up repeatedly. “The grass in the park helps me to calm down.” Even several primary school children mentioned anxiety and were very familiar with the vocabulary.

- Some young people face highly stressful events that affect their families. Missing family, crowded households, eviction, illness, mental breakdown, busy/preoccupied family members and conflict were all mentioned.

- Anxiety also affected attitudes to visiting unfamiliar places: “There are bad people. “ “Bad things happen.”

4 The positive role of teachers:

- Understanding (listening and supportive) teachers make a huge difference to a young person’s perception of the school environment.

- Students find it easier to ask for help from teachers they know and have taken an interest in them by asking questions in and out of classroom settings.

5 The pressures and sometimes discouragements that surround the drive for high grades:

- Young people feel the pressure to get high grades. This can be discouraging to some. A few who face setbacks don’t want to cooperate with the system.

- Nearly all young people were well aware that they will benefit from working hard and from perseverance, but some struggle in spite of this as they find school boring and restrictive.

6 The importance of role models:

7 Developing positive relationships:

- The research points to the need that young people have to be part of secure wider environment (community) which features positive two-way relationships which the young people can draw on when needed, and into which they are inspired to give their own contribution.

- Constructive relationships might be found in family, school, one’s friendship network or an out-of-school organised group or activity. Any of these may provide positive or negative influences, but helping each young person to feel securely attached within at least one positive environment may be an action point. Knowing that there are other people with our best interests at heart aids a sense of security.

- Attachment cannot be manufactured from nothing (research carried out by ‘Fusion’ for example suggests that young people have no desire to be ‘placed’ into mentoring relationships)5. Instead, positive relationships grow as people invest into one another’s lives.

8 Aspirations: goals and dreams

- Almost all teenagers named one or more goals, although some were limited to the very short term (e.g. school targets). Uncertainly featured strongly, also regarding which career to choose and the pathways to achieving it. Many students have limited interactions with their wider community, after-school clubs and experiences outside of Whitley.

- Finally, ‘aspirations’, goals and dreams change. Primary school children were full of boundless career ideas. These became somewhat more modest and less exclusively career focused in secondary school (family life, wealth and personal qualities also featured). Older children were more discerning and opinionated about people in their lives than the younger ones.

The findings from the youth survey in the next section provide complementary and explanatory insights into these factors.

1Reading Girls School and The Palmer Academy are both members of the Whitley Excellent Cluster of partner schools.

2A detailed report on the methodology and data analysis is available

3Ebony George from RBC also helped in developing the game and facilitating the game sessions

4The structure of the school council was presented to us by the Council Chair (from Year 6).

5Fusion 2015. Research Report into the needs of the Youth and Community of Whitley, Fusion Youth & Community UK. Reading.

4.3 Youth Survey

Participation

Thirty-eight young people completed questionnaires regarding their school experiences, thoughts for the future and barriers to progress. Half of these were from RGS, and half from JMA. They were all from years 8 and 9 (approximately 13-14 years old). Almost three quarters of the respondents were girls (which makes sense since half the surveys were conducted in a girls school). Their responses could be compared and contrasted to the responses of teachers and parents, aiding our understanding of how positive aspirations may be promoted and fulfilled.

Student happiness in school

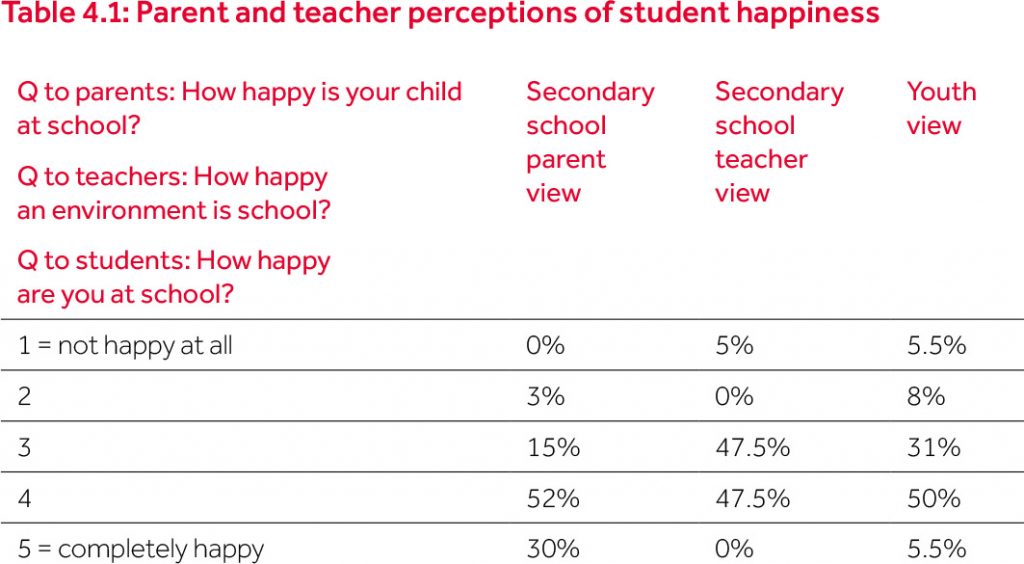

Our students did not see themselves as happy as parents rated their secondary school children (see Chapter 5). However, they reported levels of happiness very similar to the teachers’ views on how happy an environment the secondary school is (see Table 4.1).

Summary by gender

- Girls tended to be less happy than boys, although parents had not made this distinction (parents reported similar levels of happiness for sons and for daughters). Girls seemed particularly affected by relational issues in and around school rather than by the school work or by worry about future prospects.

- Particularly with peer relationships, but also when it came to approaching teachers, girls were more likely to see problems than boys. They were also more sensitive to issues in the home than boys, less likely to feel safe or feel they have a voice. Girls did not struggle more than boys with the work however, and they were not more likely to feel the school is not providing them with skills. They were just as confident as boys about getting a job and were more likely than boys to talk about moving on to higher education.

School impact on happiness

The young people were asked an open question about what affects their happiness at school.

- Their top response had to do with peer relationships, with just over half the students (and especially girls) volunteering the information that friendships made the big difference.

- The next most important reason, mentioned by a third of all respondents, was that teachers made a difference, especially the way the teachers manage the class and keep order (neither pupils nor teachers find it easy to bear disorderly classes and constant tellings off).

- This was closely followed by matters to do with the lesson subject – young people are happy about particular subjects, especially if they are good at that subject or if it was presented well. Teachers also emphasised managing well with school structures.

- Almost 20% of students mentioned that their happiness was also affected by being able to have fun in school, not only with peers, but they appreciated fun activities, special events and trips outside of the school.

Links between student responses to happiness in school and responses to other survey questions

1 School-parent and child satisfaction go together as there were close correlations between the student’s self-reported happiness at school and how positive they report their parents or guardians to be about the school:

- Just over 80% of students felt their parents were positive or completely positive about the school (the top two of five categories).

- A student’s report of being bullied was strongly correlated to negative parental perceptions about the school.

- The need for schools to address parent concerns, and the need of parents to ensure they speak in a supportive way about schools to children, are both important in the wellbeing of students. Children who were unhappy at school were more likely to be absent from school and we discuss this in a later section.

2 Happiness at school is associated with being able to identify someone to talk to in case of a problem. Most students (61%) identified a particular member of staff they would want to talk to. In addition, a few mentioned friends and just 4 mentioned family (esp. Mum). Because of the importance of school staff when finding someone to talk to with a problem at school, those finding it difficult to approach teachers were less likely to say they knew someone to talk to. 14% of respondents were not able to name someone they could go to, and 42% mentioned at least some hesitation in approaching teachers with a problem.

Of staff that were mentioned as persons to talk to, a lot of young people mentioned the same persons. Some of these may have been dedicated staff members available to listen to student concerns, but the fact that over 40% of students felt some degree of hesitation in approaching teachers with a problem suggests that further work could be undertaken here.

3 Finding it difficult to approach teachers and also the feeling of having no voice and that views are not understood and respected links with unhappiness. They also felt less happy when peer relationships were not going well and especially

if they were being bullied or did not feel safe. Broken peer friendships, the feeling that one’s views are not understood and respected, the feeling that the school is not providing the right skills for the future and feeling unsafe were also relatively widespread problems (mentioned by at least 50% of students).

Young people were less happy at school when they mentioned problems with school work, and when they felt that the school was not providing them with the skills they need for the future. Those less happy at school were less likely to mention going on to Higher Education.

4 Young people (and their parents) were happier about school life when the young person was involved in a club outside of normal school lessons. Clubs enable young people to interact with more adults who are investing in their welfare. These positive relationships with adults are also seen in school life; students who attended clubs were more confident about approaching teachers with a problem as well as being happier in school. They were also more positive about their future

prospects and more likely to think they would find a good job after school (although they were not more likely to aspire to higher education outcomes. Clubs mentioned were mostly sports related. There were just a few mentions of art and drama activities. ‘Young Researchers’ was mentioned by three students.

Student happiness at school was not affected by problems at home, by negative influences in the community, by social media issues or by disliking general class management.

Absenteeism

Students were asked how much school they missed compared to others in their class. This is how they responded to the options given:

I almost never miss school - 37%

I miss less school than average - 29%

I miss about as much school as others - 30% I miss more school than average - 4%

Although people have a tendency to put themselves in a more favourable light than is actually the case, the fact that we have four categories means that we still have some basis for comparison.

Absenteeism, which had no gender differences, was linked to being unhappy at school and it was particularly related to:

- Feeling unable to approach teachers with a problem.

- The feeling of having no voice.

- Lack of confidence about getting a job.

- Broken friendships and problems at home.

It was not linked to struggling with the work or feeling the school doesn’t equip you with the right skills, suggesting that this is more of a relational matter than a work-based matter.

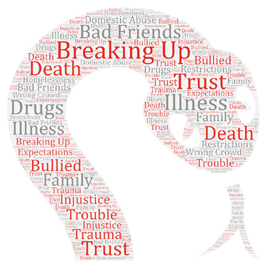

Problems for young people

We asked students about the problems they faced in and outside of school1

- Fake friends/broken friendships was mentioned by 63% of young people, with one third of these saying it was a big problem. Bullying was also mentioned by a third.

- The way that teachers managed a class was mentioned by 66% BUT mostly as a small rather than a big problem.

- 49% mentioned direct teacher-pupil relations, with one third of these mentioning it as a big problem.

- Feeling able to approach teachers with a problem was significantly associated with happiness, and this was at least some degree of a problem for 42% of students.

- Half of students did not feel entirely safe when going somewhere other than their usual route to and from school. This lack of confidence is associated with wellbeing, and particularly affects girls.

- Around half of students also see negative influences in their community as a problem (boys as much as girls this time), but this is rarely felt to be a big problem. Interestingly, those mentioning Higher Education after leaving school were the most likely to see community influences as a problem.

- 55% were not convinced that the school is providing them with the skills they need for their future, and this interacts with their happiness at school as well as their hopes for the future; 39% secondary school parents and 60% of secondary school teachers also felt that the school was not preparing pupils adequately for the future. Teachers and parents particularly want more instruction in life skills.

- Having problems with schoolwork affected 45% of students, but only to a small degree.

Clearly around half of all those involved are not confident that everything that could be done is being done in Whitley, and clearly this has important repercussions to the confidence of young people.

Home is not perceived as a ‘problem’ for most children, and problems at home do not affect self-reported happiness at school, although there is an association between problems at home and parents rating the school badly. Problems at home are also weakly associated with poor attendance. The fact that problems at home are only mentioned by 21% of children interviewed suggests

that child identity is wrapped up in the identity of their parents – the young people do not necessarily see parental attitudes

as something separate from themselves which affects their development, but rather home is part of who they are.

Despite adult concerns, the least perceived problem by students is appearance on social media. Less than 20% of students mentioned this at all, and most of these as just a small problem.

After school: higher education not seen as a pathway to a better future

When asked about life after school, 55% of students said they were confident of getting a good job after school, and 44% were not sure. For the 44% lacking confidence about getting a job was associated with: parents being negative about school, absenteeism (weak association), and unhappiness at school, general gloom about the future and not being able to identify anyone to talk to about a problem at school. It was also weakly associated with feeling that teachers are unapproachable. Students who did not feel the school was providing them with the skills they need for the future were also less confident about finding a job.

Confidence about getting a job had nothing to do with aspirations for higher education. Interestingly, young people did not associate higher education with better prospects.

When asked about what they see themselves doing after school:

- 83% of students saw themselves as being in a job by the age of 25 (or, if they were less confident, they at least mentioned looking for a job).

- More students mentioned a job/work than parents did when asked a similar question about where their students will be at the age of 19 and 25.

- 43% students interviewed mentioned Higher Education after school in the open question about what they see themselves doing at the age of 19. This is a lower number than parents (66% secondary school parents believed that their children aspired to higher education). This suggests that students are less ‘higher education’ focused than their parents believed; instead they are job focused.

- 34% of students also mentioned other things besides work or education such as buying a house/moving to one’s own house, pursuing a hobby, or travelling and 6% mentioned having a family of their own.

Students who aspire to higher education, compared to those who did not mention it, are more likely to be worried about school-work and about negative influences in their community. Wanting higher education did not make them more confident about getting a job or more confident about the brightness of their future. Somehow the students mind was not connecting higher education as a pathway to a better future. Aspiring to higher education did go with feeling happy at school however. Girls were more likely to mention higher education than boys.

How bright is the future?

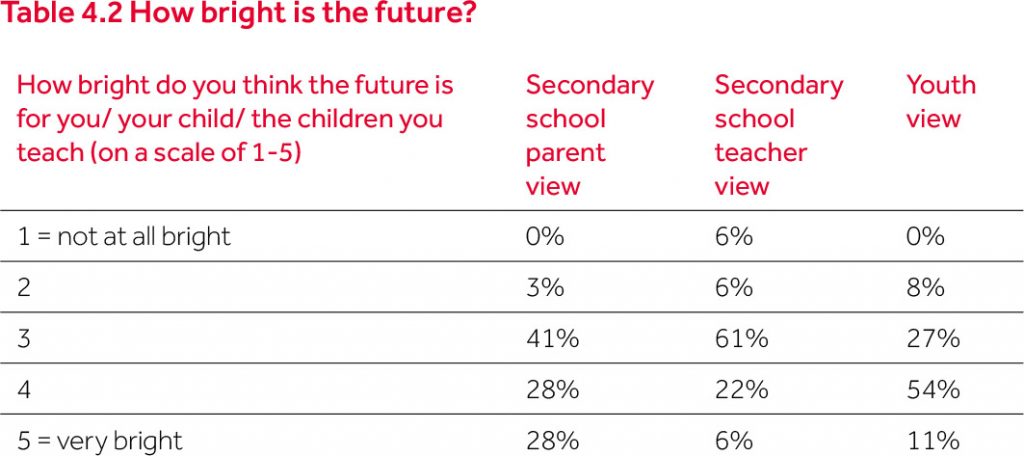

Young people judged the brightness of their future on a similar level as their parents (the particular categories vary, but overall, there was no significant difference in average response). Interestingly, both children and their parents were slightly more optimistic about the future than their teachers however (see Table 4.2).

Part of this may be because teachers were asked about young people generally, whilst parents were asked about their own specific children, who they might not want to ‘condemn’ to a poor future even in their thoughts. Whatever the reason, both parents and teachers predominantly place the prospects of Whitley children at a midway point on a scale of one to five, suggesting that there is uncertainty for the future. The majority of young people are a little more optimistic for themselves.

- Students who were happy at school and felt their parents were happy with the school were more likely to talk of a bright future. Those going to clubs saw the future brighter.

- Hopes for a bright future had nothing to do with aspirations for higher education. Parents who aspired to higher education for their child were more likely to see the future as bright, but their children did not see this association. Instead, it was young people who were confident about being able to get a good job after school who were the most positive about the future.

- Problems with school work were weakly associated with less confidence for the future, and likewise problems approaching teachers or the feeling your views are not understood or respected. Not feeling the school provides you with the skills you need was likewise associated with lower confidence for future.

- Broken peer friendships and bullying were both associated with lower confidence for the future. However, reports of problems at home or with community influences had nothing to do with confidence for the future, and nor did self-reported school attendance.

What helps and hinders you?

In a manner similar to the aspiration game, young people were asked a direct and open question about the main matters that help them forward, and the main things that holds them back.

1 ‘Relationships’ was the most frequently mentioned issue (69% of young people mentioned this). On the negative side, about half referred to friends and (less so) to family, and half referred to teachers. However, teacher impact was mentioned as a positive far more than an negative in the research overall.

Almost 20% of all students interviewed volunteered the information that having supply teachers could sometimes be problematic.

Friends on the other hand were more likely to be seen on the ‘holding back’ side than on the helping forward. Family was not mentioned much, but where it was, it was rather on the positive side than the negative.

2 Linked to relationships, mentions were also given to anxieties versus a positive mindset. Kindness and other life skills (like listening skills) were also seen to be important. 38% all students interviewed mentioned such issues – nine in a positive context (life skills, positive thinking) and six in a negative (anxieties, lax attitude).

3 Getting good grades or a job - 42%. Getting good grades was seen as helpful, along with talent and the aspiration for a particular job. Not getting good grades was also mentioned as a problem, but people rather mentioned grades when they were getting on well.

4 Other issues that hold you back included racial discrimination, and two mentioned medical issues that held them back. There were 3 mentions of the school environment as being helpful, one mention of school in a negative sense and one frustration with age rules.

Once again, it can be seen that relationships come out as a top factor affecting young people’s happiness and how they see

their future. Everyone agrees to the importance of supportive relationships – the harder bit is making sure everyone is linked in

to them. Teachers were particularly strong on the importance of parental influence, although students barely mentioned this (perhaps because their home and family life actually constitute their own identity). Parents mentioned money barriers but this was not an issue mentioned by young people.

In summary: happiness shapes future views

Our surveys with young people supported much of what we learnt playing the aspiration game but they allowed us to make some additional conclusions around the role that happiness plays in shaping aspirations and life chances.

1 Unhappiness in school was related to being less likely to hope for a bright future by parents, teachers43 and children and unhappy young people are less likely to aspire to higher education and be less certain about getting a job.

Girls reported in significantly less happy than boys at school, and were particularly affected by issues to do with relationships. They were not fazed by the schoolwork or future prospects, and they were more likely to see themselves in higher education. To improve the wellbeing of girls, it is clearly important to address relationships.

2 Children were not as happy as parents believed (only 18% of the secondary school parents interviewed did not rate their child happy at school) and with the school environment not being rated as a happy place even by half of the teachers (see Chapter 6). It is worth looking at which factors are involved in this.

Students were particularly unhappy at school (as well as less confident about their future) when:

- Direct personal relationships were affected. Almost two thirds of young people said they were set back by problems with peers, and one third mentioned concerns with bullying.

- They felt that teachers could be more approachable. Almost half of young people mentioned this.

- They also feel that are they misunderstood or disrespected. Almost half of students expressed problems in this area.

- Feeling less happy at school and less confident about the future was also associated with not being able to name someone to talk to in the event of a problem. Over one third of students could not identify someone. Being in clubs is associated with more positive outcomes, although almost half of the teens interviewed were not linked to extra-curricular activities.

Having supportive, personal connections with peers and adults is clearly important.

3 Parental negativity about school was associated with children’s negativity about school and about the brightness of their future. Teachers were also keen to point out that whether parents support their child and the school in their child’s education affects outcomes. This survey does not negate the idea that how parents talk about the school in front of their children makes a difference.

Parental negativity about the school was also associated with children not feeling they can approach teachers.

4 Having said all this, a report of problems generally at home was not associated with unhappiness at school, nor was it associated with reduced hope for a bright future. This fits with a point made at the community panel run by the Young Researchers (see Chapter 7) “wherever you start from you can still go forwards”. It would seem that the school can still be a good place to be even when things are hard at home. The way parents talk about school is something important that parents might quite easily change.

Problems with the school work were associated with student unhappiness at school and lack of confidence about the future, even though students reporting problems were often those who hoped to go on to higher education. Young people feel the way lessons were presented made a lot of difference to the subject.

5 Young people were also not happy when they felt that schools were not equipping them with skills they need for the future2, and feeling this lack of upskilling was closely associated with uncertainty about getting a good job. Around half of students, teachers and parents agreed that the school could do more to prepare pupils for the future, the area of life skills being particularly noted by parents and teachers as an area to improve.

6 Unhappy children were more likely to miss school, which has a negative association also with their hopes for getting a job after school. Absenteeism was particularly marked amongst children who were unhappy in their relationships, both in school with peers and teachers, and also at home. Absentee students were more likely to have a problem approaching teachers and to feel that their views were not understood or respected.

Certainly external studies indicate how having a mentor show a personal and informed interest in the day to day progress of a student affects both grades and attendance3. (Schools simply sent a text to the mentor about what is going on in class to help the mentor to talk to the student about school work).

7 Young people did not necessarily see higher education as a route to better outcomes (outcomes like confidence in getting a good job or having a bright future). There was no positive correlation between student aspirations for higher education and expectation of these outcomes, even though there was a positive association when the same questions were asked of parents. Parents also tended to think their children wanted higher education more than the children themselves -receiving more direct information from universities might help both. At present, 43% of students mentioned higher education when asked what they saw themselves doing at the age of 19, and this was connected with being happy at school.

8 Less than 20% of students saw social media as any kind of problem and problems at home were also given little importance. Like their parents, children resisted the idea that their background held them back. The sense of being in control of one’s own future is positive, although learning not to feel pressurised by things that are beyond personal control is also important to wellbeing. Moreover, it is clearly a misperception that Whitley young people have low aspirations.

More to the point is directing them on the pathway to sustaining and achieving their aspirations. Good connections and adult time to listen to young people can help with this:

- Approachable teachers with good soft skills are of great value. It was good to find that more students remarked on teachers in a positive light than a negative light.

- Young people may benefit if schools give dedicated time to teachers to deal with out-of-class issues.

- Parental attitudes to school matter since children's approaches are intimately bound up with their parents.

- Extra-curricular clubs seem to be beneficial too – they are another way of giving adolescents positive contact time with adults.

1These potential problems are placed roughly in order of the number of mentions they got, although not necessarily in order of the negative impact they had on the student.

2It might be the case that students with a negative attitude about the future may be less motivated about being at school and therefore interact less positively with others and with the work. Our analysis notes correlations, not causality, but whilst being cautious about jumping to conclusion it is still of value to note what factors are particularly associated with unhappy youth.

3Soon, Z., Chande, R. and Hume, S. (2017) Helping everyone reach their potential: new education results Behavioural Insights Team [online] http://www. behaviouralinsights.co.uk/education-and-skills/helping-everyone-reach-their- potential-new-education-results/

4.4 Conclusions

Through their aspiration game and student surveys, the Young Researchers helped us gain rich insight into the hopes and fears that young people have about their future life chances. In addition to the everyday stresses facing adolescents, such as getting good grades and peer pressure, some young people also have to cope with a testing social and emotional environment at home. Young people need help to develop coping strategies and resilience to deal with anxiety and stress, particularly young women.

Young people also need good relationships with people who believe in them and who have their best interests at heart. Positive two-way relationships between young people and their families, teachers and peers have an important impact on young people’s well-being, happiness, and belief in a bright future. Bullying was frequently seen a barrier to reaching goals. We have also shown significant links between good parent-school communication and engagement in school, better student behaviour and higher aspirations.

Many young people needed greater support to navigate the different pathways into work, training and Higher Education but they want to have a central role in shaping how this is delivered – having a voice is also important.

Box 4.1 Youth – SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

- Children were less happy at school than their parents thought, and this was associated with less bright hopes for their own future, less confidence about their job prospects, less aspiration to higher education and higher levels of absenteeism.

Happiness at school was correlated to:- Positive peer relationships (almost two thirds of children mentioned problems with peer friendships, and one third mentioned concerns with bullying. Young people do not feel that bullying problems are adequately addressed). More work needs to be done to reassure children that bullying is being addressed.

- Feeling that teachers are approachable and feeling understood and respected (almost half of students express problems in these areas). Approachable teachers were appreciated. Over one third of students could not identify someone to talk to in the event of a problem at school.

- Being member of an extra-curricular club (almost half of the students interviewed had no extra-curricular formal connections. Many young people also did not have much experience of life outside of Whitley. This may add to a sense of insecurity – half the students did not feel safe about venturing off their usual routes to and from school).

- Managing well with the school work, and liking the way work is presented (45% students interviewed expressed struggles with schoolwork and 65% with class management).

- Feeling that the school is providing relevant skills (55% students (as well as teachers and parents) felt the school could do more to prepare pupils or the future).

- Girls were less happy at school than boys, being particularly affected by difficulties with interpersonal relationships. However, girls were more likely than boys to anticipate going on to higher educations, in spite of their negative feelings about school.

- Relationships at home matter. Many homes were crowded and some stressful situations were mentioned. Problems at home did not necessarily mean that students saw school as a bad place to be and were not associated with young people being less positive about their future. However, parents who talked badly about the school have children who are less happy at school.

- Poor relationships (both at school and at home) were associated with absenteeism.

- Social media was the least important issue in the eyes of young people (less than 20% of them identified it as a problem).

- Less than half of the students interviewed saw themselves in higher education at the age of 19. Students hoping for higher education did not expect better life outcomes than others. They need a better understanding of the link between higher education and better prospects.

- Young people felt many uncertainties regarding their future career and pathways to achieving their aspirations. Anxiety (also stemming from wider circumstances) was widespread. They wanted opportunities to test different pathways and find their own way forward. They wanted space for constructive two-way conversations. They wanted a voice.

- Introducing positive role models that relate to the lives of young people in Whitley was seen as an important help in finding direction. These can also counteract the influence of negative role models in the locality, helping young people to distinguish the outcomes they want.

- Students felt under pressure to get high grades. Those who did not were discouraged. They need advice and direction appropriate to their circumstances. Young people were aware of the benefits of hard work and perseverance, but some still struggled as they found school boring and restrictive.

- Young people in Whitley were generally aspirational, rarely feeling that their circumstances or background held them back. Aspirations change however. They became more modest and less exclusively career-focused as children turned to young people. Young people were also more discerning about the people in their lives than children.