5.1 Introduction: conversations with 136 local parents

The aims of this strand of the research were to understand the role of parent-school/teacher relationships in South Reading and to investigate how these relationships shape parental aspirations for their children. This was undertaken via:

- • A questionnaire survey with 122 local parents in face-to-face interviews.

- • 14 in-depth semi-structured interviews that informed the questionnaire.

- • Reflections from meetings, workshops and community events. This chapter explores the key findings1 from our parent responses.

1A more in-depth and detailed report on the analysis of parent’s questionnaire and interviews is available on request from [email protected]

5.2 Parent’s experiences of their children’s schooling

In total, 122 parents participated in the face-to-face survey undertaken by the Whitley Researchers in a range of community and school locations (see Chapter 3). The majority were parents of children in primary school, but 29% (35 individuals) were parents of children in secondary school.

The questionnaire was biased to a female point of view since three quarters of all those interviewed were women, and 62% of the children they referred to were girls. However, there were enough male representatives in the sample to check if there were major differences in response by gender.

The majority (55%) of those interviewed had two children in the home, although 29% of the sample had more than two children. The questionnaire was filled in only for the oldest pupil to keep the responses focused. The children in the sample ranged in age from 4 - 16 years, with the biggest representation from 8 and 9 year olds.

In addition to these questionnaires, the in-depth interview participants were mainly mothers (11 compared to 3 fathers), aged between 25 and 55, and with children in both primary and secondary schools.

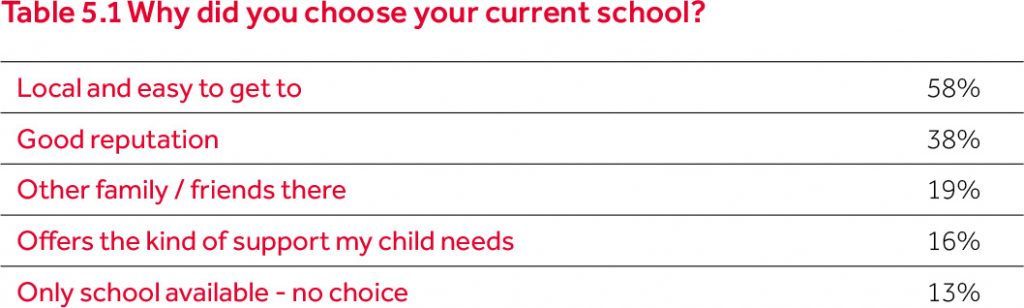

Why this school?

58% of parents chose their children’s school in South Reading because it was local, accessible and 38% based on good reputation.

Parents who chose their school on the basis of reputation were more likely to report their children as ‘happy in school’ and more likely to report positively on the approachability of teachers.

The most important reason why parents picked the schools they did was having the school close by (see Table 5.1). Whether parents felt the school had a good reputation was also an important factor.

16% of parents selected the school because they hoped it would provide the type of support their child needed. This issue often surrounded catering for the special needs of a child.

Only 13% of respondents sent their child to the school they did because they ‘had no choice’ - with the greatest negativity surrounding a couple of primary schools and less so the secondary schools, even though Whitley’s secondary schools were rarely chosen because of ‘good reputation’.

Parents who selected none of these options mostly selected the school after visiting and getting a positive feel for it. All this suggests that most parents interviewed are not resentful about their child being in the school they are at.

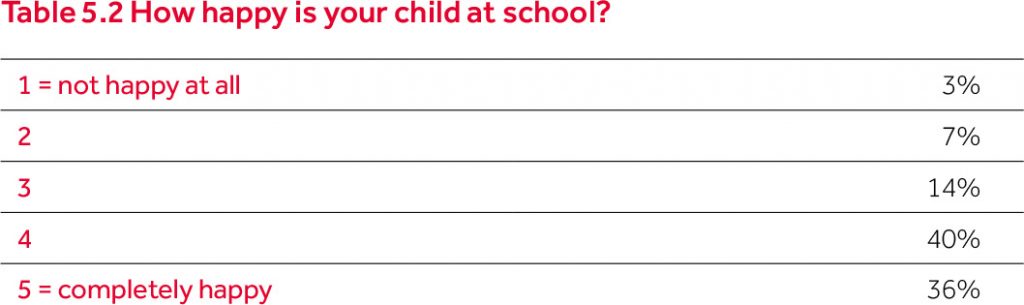

Children’s happiness:

Over three-quarters of parents felt their children were happy.Approachable staff, happy children and having chosen the school on the basis of reputation (feeling the school is a good school) were all interconnected features.

As shown in Table 5.2, the majority of parents felt their children were happy at school. Over three quarters of parents put their children in the top two categories for happiness (40% and 36% respectively). Parents who had been happy at school were more likely to report their children as being happy at school:

When asked an open question about what influences happiness, the most frequently cited conditions were said to be:

- Managing well with lessons

- Having encouraging teachers

- Having good peer friendships

How well children managed in these three areas was partly attributed to personality or personal attitude, and partly

to conditions outside of the child’s control. The perceived approachability and efficiency of school staff was closely linked to reports of happier children.

Communications and relationships between school staff and parents

Communication between parents and schools is influential in matters such as parental engagement in school events and satisfaction with their school. Parents who felt well informed by the school were more likely to report their child as happy in the school.

79% of parents feel that they have sufficient information from their children’s school.

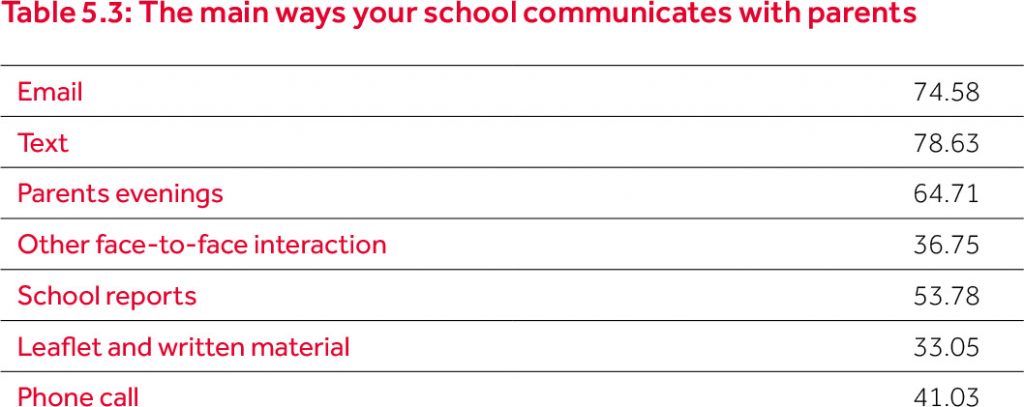

Although text is the most cited mode of communication between schools and parents, there was a statistical association between receiving letters home and the feeling of getting enough information.

Text is the most cited mode of communication between school and parents, with email in second place. Face-to-face communication through parent’s evenings is also cited by 65%. It is interesting that only 54% parents ticked ‘school reports’ as a main mode of communication. Are half the parents not even reading the reports the school sends out? Or do they not find them meaningful?

It was interesting to find that different parents noted different ways of communication for the same school, suggesting that different people latch onto different ways of communication, and a multi- dimensional approach is appropriate, given that many channels of communication go unperceived by some parents.

21% of parents did not feel that they received enough information from the school that is useful to them and especially parents of children in a minority of primary schools.

There was a general feeling among this minority of not really knowing what their children were up to or where they were academically. This feeling applied especially to people who were simply not getting the information that is available but also to a minority who were getting all the information coming in, but wanted to be more involved in the education of their child.

It was interesting that parents in receipt of the least common mode of communication – leaflets and written material – were the ones most likely to say that communication was sufficient. Letters home may not yet have had their day then.

Messages to one’s phone were the second most likely form of communication to correlate to the feeling that enough information is getting through.

Some parents who did read school reports felt that they were not detailed enough or were impersonal. They would prefer more face- to-face time with their child’s teacher – although they appreciated that teachers already have so much to do. Speaking to staff personally was, for a small number of parents, a valued link with their school. As one father commented:

"I would like better and more communication. I would LOVE to have more meetings with the teachers" (Father, aged 25-35)

A number of parents felt that they would like to have more notice about school events and assemblies due to work commitments, more careers advice and updates of when their children had done well. Some suggested that they might keep up with their child’s progress via homework that the parent can engage with. It could be seen from later data that parents who felt that communications were good were significantly more likely to make it to school events.

Research outside of this project on young people has shown that texting a ‘study supporter’ (which can be a parent) with information about school work can have a significant impact on final grades, as well as on school attendance. Parents find out which upcoming tests they need to ask after and show interest in, which can encourage the child to study.<sup1 Text is a particularly valuable source of communication because it is extremely likely to be read, it’s short, and does not require access to a PC or sign-in. However, modes of communication that require parents to download a particular app, are less likely to be accessed<sup2.

Parents who felt well informed by the school and via multiple channels were more likely to report their child as happy in the school. The perceived happiness of children was also very closely related to how well parents felt that school staff handled their concerns. It is not clear from this whether good parents of happy children also read communications and collaborate well with teachers, or whether good teacher communication is the driver of child (and parent) happiness. Probably neither factor should be disregarded.

Whitley Researcher: What do you think the barriers are to having a good relationship with school?

"Bad or lack of communication between school and parents. This is the main barrier. Without proper communication, teachers can be misunderstood and parents might feel neglected or feel the school does not care enough" (Mother, aged 25-35)

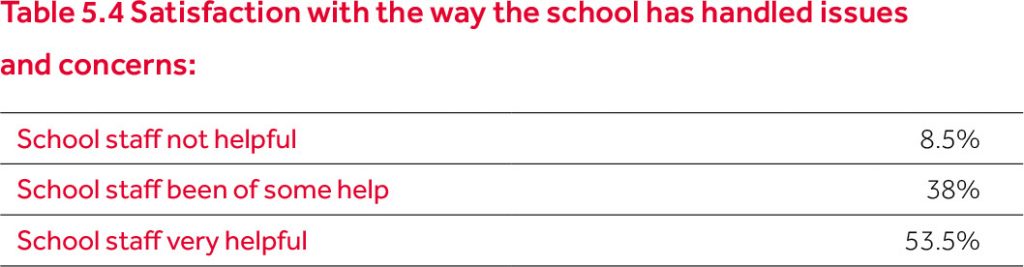

Just over three quarters of the parents interviewed had experienced a school-related concern. A small minority of these (5%) had not mentioned this concern to the school, and of the rest, there were varying degrees of satisfaction regarding how the school handled their concerns.

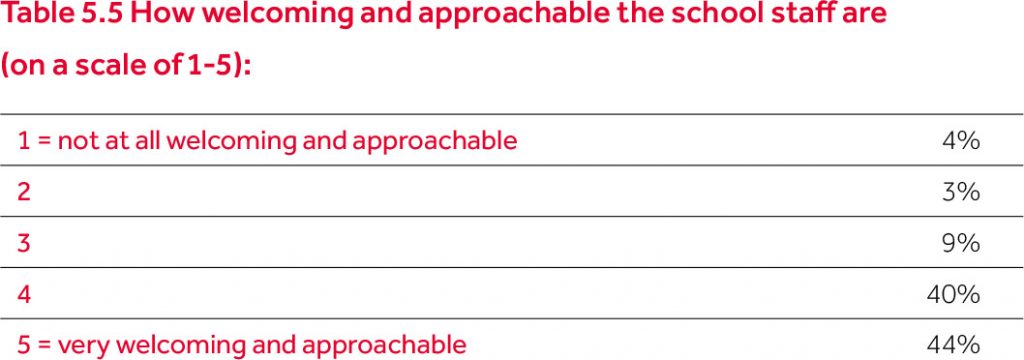

The majority of parents interviewed (84%) feel that school staff are welcoming and approachable, both in primary and secondary schools (although relationships tend to become more distant in secondary schools). Where the score was less than 5, parents often mentioned particular staff members who spoilt the atmosphere even though they felt appreciative towards the majority of staff.

Although most people felt that school staff were helpful, 8.5% of respondents who had raised a concern did not feel that school staff had been at all helpful. These persons were also negative about the approachability of school staff, suggesting that parent-teacher relations are (or became) tense in such instances.

The Importance of Staff Approachability and School Support

Parent perceptions of school staff approachability is the most significant factor that shapes parent’s optimism about their child’s future and aspiration for their child to go on to Higher Education.

84% of parents feel that school staff are welcoming and approachable, both in primary and secondary schools (although relationships tend to become more distant in secondary schools).

Nearly half of all parents felt that schools could perform better for their children.

It’s good to know that most Whitley parents feel that school staff are welcoming because when it came to a parent’s optimism about their child’s future, and also when it came to parental aspirations for their child to go on to Higher Education, our data tells us that the approachability of school staff is the most significant factor:

- The quality of staff in terms of their approachability was much more important a factor than how good the information flow was between teacher and parent.

- Staff approachability and successful communication were related to how likely it was for parents to attend school events with their child, even controlling for parental school background.

- The ‘soft skills’ of teachers matter to school experience, parental engagement with the school and with the future outlook of children in their parents’ eyes, and this retains some effect even where parents are not getting all the school communications.

Despite the mostly positive reviews on school staff, nearly half of all parents (and particularly mums) still thought that the school could perform better for their children. The other just-over-half were satisfied with things as they were.

The remainder were asked an open question about what the school could do more as highlighted in Box 5.1. Issues included better preparation on life after school, information on qualifications and information, training in life skills and better transitions to secondary school. This wish was especially strong amongst parents who had not had a good school experience themselves.

Box 5.1 – Parent’s views on school improvements

- Catering for the brighter3 children. It was noted that a lot of resources get sucked in by children with bad behaviour, and some concern was expressed with the academic progress of children.

- Child and parent-friendly (listening) approach of staff. It was noted that teachers are quicker to feed back negatives than positives.

- Extra homework and information to help parents engage where desired (this idea had several mentions). Also getting parents into the school to work together with their children. Some parents had a real desire to work together with teachers in the education of their child but were not sure how to engage.

- Having more one-to-one help available for children to get their work done which includes having more teachers to spread the load. It was noted that teachers are overworked and under resourced.

- Ensuring good behaviour and some focused training for children in support of social behaviour which is specially resourced.

Also having more sport, tackling bullying, helping children work through loss and to gain confidence. - It is hard for working parents to get to events or to contact the school after work.

Child behaviour

Parents were asked an open question on their child’s behaviour at school. The question was, ‘If and when your child gets into trouble at school, what are the biggest contributing factors?’

Almost half the parents responded that their children did not even get into trouble at school4. The other half mentioned three main issues in order of frequency of response:

1 In first place, the child’s own choices or lapses - included forgetting school equipment, falling out with other children, acting up in class, losing concentration, distraction with peers, inappropriate dress, not doing homework or getting to grips with work generally, and not getting along with teachers. It also included special needs related behaviour problems and simply not understanding what they were supposed have done (mentioned multiple times and suggesting a communication problem).

2 Peer influence.

3 Poor staff management (but only mentioned by a handful of participants).

Gender did not make much difference to the likelihood of having been in trouble at school although if anything, girls were less likely to have experienced getting into trouble.

The move from primary to secondary school made little difference in the likelihood of children misbehaving but there were some differences:

- Primary school: children in primary school were less likely to have misbehaved where their parents were helping them with homework or engaging with the school by helping with a school event.

- Secondary school: parents tend to be less ‘hands on’ and these forms of engagement were not predictors of behaviour. Getting into trouble and feeling that school staff should do more to support children went together – perhaps these parents were expressing a felt need for help.

In the interviews, parents mentioned the transition to secondary school as a particular area of concern:

"Primary schools are failing to prepare children for secondary" (Mother, 45-55)

Parental engagement with the school is influenced by communication

54% of parents stated that they were not at all likely to help with a school event.

Parents who reported good communication with the school were more likely to help out with school events, attend school events and send their children to school clubs.

Parents who were in good communication with the school (who felt that school communications were sufficient) were more likely to help out with school events, attend school events and send their children to school clubs.

In terms of parental engagement with the school, parents were asked whether different forms of engagement were likely, possible or unlikely to have happened in the last month:

- 86% of primary school parents and 52% of secondary school were likely to have helped with homework.

- 84% of primary school parents pick up their child from school

- 50% of all parents attended schools event or sent children to a school club in the last month.

- Only 40% had spoken to school staff.

- 54% of parents were ‘not at all likely’ to help out with a school event (only 12% were likely to do this and this was mostly at primary school).

People whose own experiences in school had not been positive were less likely to attend or help with school events.

One’s own past experience of school also affected the likelihood of helping children with homework – parents who had had a good experience of school themselves were more likely to engage in this way.

Helping with homework, picking the child up personally and sending the child to clubs tended to run together. Parents who did these things were also more likely to aspire to higher education for their children. Households where a member of the family was working were more likely to get their children into clubs.

Parents of children who went to a school club were not only more engaged with their child’s education, they also rated their child as being happier in school and were more likely to believe their child aspired to higher education. A statistically significant link was still found between children attending school clubs and child happiness at school; also between children attending school clubs and children wanting to go on to higher education5.

This suggests either that aspirational and happy children go to school clubs, or that clubs contribute to happy and aspirational children.

Parent and Child Aspirations: hopes for the future

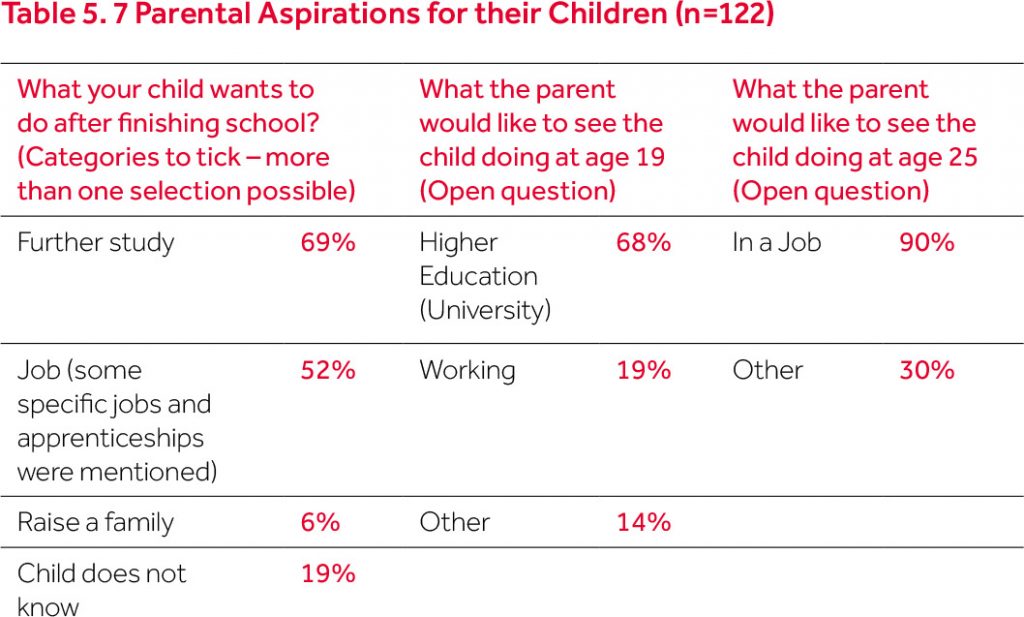

Parents were asked about what their children wanted to do after school, and also about their own aspirations for their children in the future.

1Soon, Z., Chande, R. and Hume, S. (2017) Helping everyone reach their

potential: new education results Behavioural Insights Team [online] http://www. behaviouralinsights.co.uk/education-and-skills/helping-everyone-reach-their- potential-new-education-results/ The specific study involved young people needing to retake Maths and English GCSEs. Over 1,800 students in 9 institutions took part, half of which were sent texts and half were not. Comparing students whose study supporters were and were not texted, the supportive text messages resulted in a 7% increase in attendance and being 27% more likely to pass their exams.

2Sanders, M. & Groot, B. (2018) Why text. The Behavioural Insights Team. [online] http://www.behaviouralinsights.co.uk/trial-design/why-text/

3Dorling, D. (2010) Injustice: Why social inequality still persists. Policy Press: Bristol . See Chapter 3 for discussion on ‘ability’

4The questionnaire only asked about whether a child had been in trouble at school and not the severity of the issue.

5This assertion is based on regressions with either ‘child happiness’ or ‘child aspiration to higher education’ as the dependent variable, and ‘attendance of a school club,’ ‘parent aspiration for child to go on to higher education,’ ‘parent helps with homework’ and ‘parent experience of school’ as independent variables. Even controlling for the parent variables (some of which became insignificant) attendance at a school club still had a statistically significant interaction with positive outcomes for the child.

5.3 How bright is the future? Parent’s hopes for their children

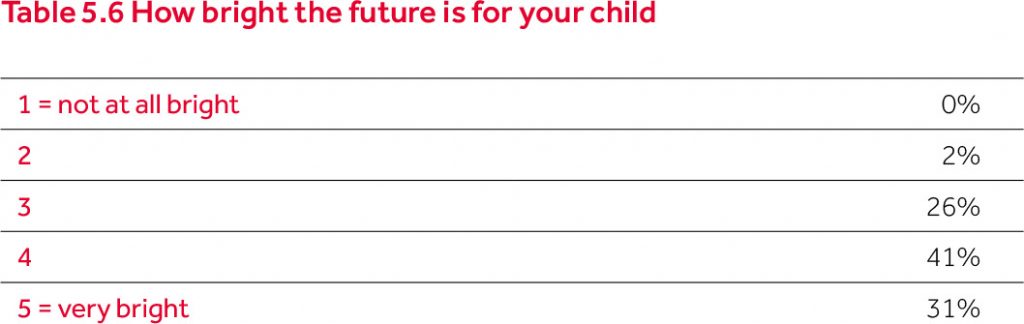

72% of parents see a bright future for their child.

68% of parents would like to see their child in Higher Education when they are 19, but these figures reduce during secondary school.

Hopes were especially high for children whose behaviour was good and who had welcoming and approachable teachers.

Parental aspirations drop as children move through secondary school.

Parents of all backgrounds and experiences were equally likely to imagine a bright future for their child. Feeling that a child lacked opportunities rather dampened this optimism, and so did the feeling that children were not happy at school.

Hopes were especially high for children whose behaviour was good and who had welcoming and approachable teachers, who parents felt were doing all they can. Parents who imagined a bright future for their children were also likely to aspire to Higher Education for their child.

Around 70% of parents thought their children would want to be doing further education after school, and around the same number hoped this for their children themselves. The majority of those mentioning Higher Education did not specify which form (for many of them, their children were only in primary school), but of those who did, 23 parents mentioned university and 16 mentioned college. University aspirations are clearly not off the radar for Whitley parents.

Having said this, these aspirations for University appear to be less than the UK average. A review of parental aspirations for primary school children in other parts of the UK suggested that over 85% hoped their child would go on to further education, although the way the question was asked could have influenced the response1.

It was observed in this external study that parents who had not been in Higher Education themselves and also who had never worked were less likely to have mentioned Higher Education for their children. These are issues that may also apply to some Whitley parents.

Indeed, in this study it could also be seen that parents with a bad school experience themselves, or who had no one in the household in a job, were less likely to aspire to Higher Education for their child.

As children moved into secondary school, aspirations dropped. Parents of secondary school children were less likely to hope to see their child in higher education. This is in keeping with trends in other parts of the UK. Perceived lack of ability is also associated with less expectation of going into higher education.

On the other hand, 90% of Whitley parents aspired that their children should be in a job at the age of 25, which is higher than was noted in other parts of the UK where only just over 80% of parents mentioned this aspiration for their child. Only very few mentioned travel opportunities for their child – far less than in other parts of the UK.

A significant number of parents were vague about the specific direction of their child’s future – wanting only that their child is ‘doing well’, happy and fulfilled, which are all important goals and equally as valid as going to University:

"I just want my child to discover what she is good at and what she needs to work on a bit. I would like her to reach her full potential" (Mother, 25-35)

However, lack of specific direction and the feeling that their child did not know what they wanted to do tended to be associated with parents who had had a bad school experience themselves or who had no one in the household working. There were no significant gender differences.

Barriers to aspiration

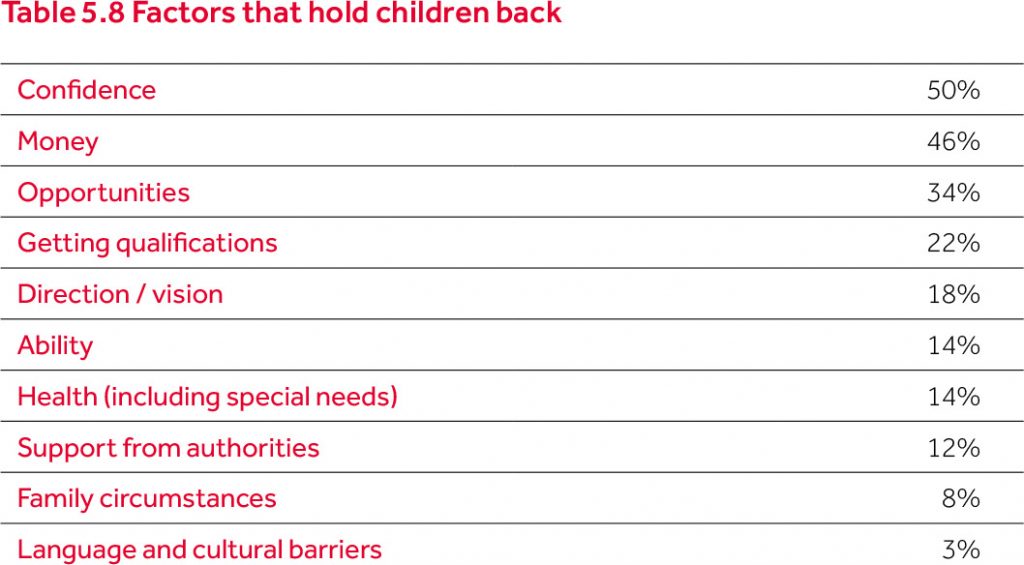

‘Lack of confidence’ and ‘money’ seen as holding children back by half of all parents.

Monetary barriers included costs associated with going to University and after school clubs, expensive local housing and austerity and government cuts impacting on youth provision.

Parents own poor personal experiences of school were linked to less aspirations for their children to go on to Higher Education and being more likely to say that their child ‘does not know what to do’ after school; they were also less likely to send their children to after school clubs.

Out of the options available, parents selected the following issues as things that hold their child back (here presented in order of priority):

Lack of confidence (linked also to anxiety and fear of failure) is a major issue with is seen to hold children back:

- There was no significant difference between boys and girls.

- The problem was noted in primary schools as well as in secondary schools.

- Lack of confidence was rather associated with good behaviour than bad behaviour – misbehaviour and confidence went together!

Money: lack of money is another significant issue. Parents mentioned the costs associated with:

- The costs associated with going to University.

- Expensive housing, such that it is hard for young people to launch out independently.

- Government cuts were seen to be damaging the prospects of young people.

- Costs of after-school clubs and transport.

Money barriers may also link to the cost of giving children the opportunity to try new things. Lack of opportunity was another important reason why Whitley parents felt their children were held back:

“Limited experiences at home and with family can limit a child's achievements so I try to do as much as I can" (Mother, 45-55)

Getting qualifications followed by direction/vision were the next most important issues, especially for secondary school pupils:

- However, it was not the case that parents who felt that their child lacked direction, were less likely to hope their child would go on to Higher Education or to believe their child wanted this.

- Some parents were more worried about their child lacking direction ‘(mucking around in class’ instead of focusing on their work) when they had high aspirations for their child.

As one parent commented

"I would like to teach my child to work hard and to not be indifferent to education. I want her to have ambition. My thoughts are that schools do not teach ambition” (Mother, aged 35-45).

Ability and health (often talked about in terms of special needs) were the next two barriers perceived to face children, followed by support from local authorities. Parents who felt their child faced barriers in terms of ability were also less likely to say they hoped their child would go on to higher education. It was interesting to note that family circumstances came after all of these – understandably parents did not like to say that their own family circumstances were holding their children back, but our research with young people showed that this can be a significant factor.

Family circumstances and parental school experience, including what the parent’s own school experience was like, and the occupation of members of the household, were also linked to perceptions regarding their child’s experience, with parents who were unhappy at school being more likely to say that their children were unhappy also.

Moreover, poor personal experiences at school were linked to:

- Less parental aspiration for the child to go on to Higher Education.

- Being more likely to say that their child ‘does not know what they want to do’ after school.

- Being less likely to pick up information from multiple channels

- Having a poorer perception of teachers and their ability to fix the things that concern them.

- Being less likely to be engaged with school in terms of attending or helping out with school events.

- Being less likely to send their child to a school club, some of which may be due to simply not being aware of what is going on (parents in this category were less likely to say that information from schools is sufficient).

- Being less likely to help their children with homework.

Poor school experience was also linked to the feeling that money is a barrier to their child’s progress, to not having anybody in paid work in the household and to picking the school just because it was local.

People who had had a difficult school experience themselves were not more likely to expect their child’s future to be bleak, they were not more likely to say the school should be doing more to support their child or to blame staff for their child’s misconduct, they were less likely to blame peers for behaviour issues, and they were just as likely as everyone else to hope to see their child in a job in the future.

Parents clearly still hope for good for their child, and they can still be positive about the overall education of their child despite some difficult relations with school staff, and yet struggles with the education system tend to persist from one generation to the next.

Parental concern for the welfare of their children came over very strongly in the surveys in spite of sensitive family circumstances which parents refused to discuss. It is not helpful for teachers to assume that because of tragic and chaotic family circumstances that the parent does not care about the welfare of their children – this just wrong-foots people and puts them on the defensive. Assuming the best could help ease communication.

Mothers were more likely to perceive barriers for their children than fathers, and boys were perceived to suffer more from lack of direction (linked to bad behaviour) or difficult family circumstances than girls.

A few parents resisted the idea of children facing barriers at all. They felt it was wrong to have anything holding a child back. One parent added “Parents and school’s role is to give direction and vision, although the future is ultimately all down to the child.” Another said, “Anything is possible.”

The idea that there is always a way forward from any situation is important to keep in mind, without neglecting to improve the things we can for children. As one parent noted about the taking part in the survey, “it has given me questions to ask myself how best to help my child.”

1Bradshaw, P., Hall, J., Hill, T., Mabelis, J., and Philo, D. (2012). Growing Up in Scotland: Early experiences of Primary School, Edinburgh: Scottish Government. [online] http:// www.gov.scot/Publications/2012/05/7940/13

5.4 Conclusions: The links between parent- school engagement, family circumstances and positive aspirations

The data clearly tells us that there are a number of interrelated factors that are working together to influence parent’s feelings about school and aspirations for their children: good parent-school engagement/communication, school ethos and parent’s own experiences and family circumstances shaping aspiration and hopes for their children’s life chances.

Parent/School Engagement:

Firstly, our research shows that how well parents engage with the school and positive aspirations regarding children were found to go together. Parent-school engagement is therefore an issue of importance, and both parents and school/teachers have a role to play in this. Moreover, school-parent communication is linked to happiness and higher aspiration.

Staff Approachability: Regarding teachers, a welcoming and approachable attitude was strongly linked to a child’s perceived happiness at school, to whether parents think the school does enough to support their child, to how well parents engage with the school, to parental aspirations for the child and to belief in a bright future for the child. Whatever the family circumstances, these associations still held. The soft skills of teachers and their mode of relating to children and parents are therefore very important – and even more important than whether or not parents were picking up on all the school communications they should have been.

School-Home Communication: Having a parent showing active interest in school life (asking the child all the right questions) is linked to the child doing well in school, but parents need to feel informed and up to date for this. Most parents were happy with the information flow from school, although 21% felt there is insufficient information. This was, to a large extent, because of not picking up on the information that is already out there. It would seem almost half of parents interviewed were not even aware of school reports for example, or at least, did not see them as a significant form of communication.

Parent engagement with child’s learning: It also takes time for parents with their first child at school to get to grips with how things work at school, and some simply have not understood the system yet. A few parents who want more information do take in all there is however, but just want the opportunity to engage more with their child’s learning – perhaps through homework that they can do together with the child. Just because parents had had face-to-face time with teachers in the last month did not make them more likely to feel they had sufficient information from the school, although for a small minority of parents this was the only way they picked up any information at all. Working parents felt they needed more notice of school events so that they could plan attendance into their time.

Parental Background and Poor Experience of School: Regarding parents, indicators of difficult family circumstances (such as parents having had a bad experience of school or no one in the household working), were related to a less good school experience for the child, less good parent engagement and communication with the school and less high aspirations for the child to go on to further education (although we don’t see aspirations towards HE as a particular ‘goal’).

Parents are well aware that their involvement in education matters to child outcomes. However, most parents resisted the idea of child aspiration being limited by family background or at least, they resisted the idea of their own family circumstances holding their child back. Parents in general were more likely to quote barriers related to confidence, lack of money and opportunity, and the need for their child to knuckle down to work at school. They did not tend to blame teachers.

Without negating the fact that parental background affects parent-teacher relationships and child aspiration, it is important not to wrong-foot parents by insinuating that they do not want to do their best for their children. The concern of parents for their children came through very strongly, regardless of family background, and this provides a positive starting point for parent- teacher relations. How welcoming and approachable staff are makes a great deal of difference to the on-going school-parent relationship.

Family support: As we’ve explored in the previous chapter on young people’s experiences, a number of families in South Reading have experienced traumatic events and they need more support. Parents facing difficult family circumstances are the least likely to feel that they have enough information about what is happening to and for their children, and this may be contributing to their lack of engagement with school events and clubs.

Parent/school communications: Special measures may have to be taken to improve the information flow, including the use of written material. Leaflets and letters, although now the least popular mode of communication between school staff and parents, still remain the best form of communication in terms of helping parents to feel in the loop. Telephone or text contact has also been used to good effect, and is the method of communication that parents are most likely to have picked up on. Texts can also be used to good effect to send micro-information to parents of children who are falling behind, helping them to engage in discussion with their child about school work. It helps if school staff pick modes of communication which do not require parents to do something proactive (like download an app) in order to participate1.

School Support: Almost half of all parents wanted schools and teachers, to do more to help their children prepare for life after school, and this was not only with careers information, but also with life-skills and the general management of their affairs. Parents who had not had a good school experience themselves particularly expressed this2. It would seem that these parents hope teachers can fill some of the gaps they know exist in preparing their child for life after school. Attention to this area (and provision of special funding to make it happen) could be an important way of breaking the cycle of intergenerational disadvantage passing from parent to child.

However, schools/teachers alone are unable to provide all this additional support and we need to find new mechanisms for supporting young people outside of formal education. In Chapter 7, we discuss the importance of community organisations and service providers in providing training in lifeskills, confidence building and connecting them to employers.

Parents, therefore, are clearly open to the idea of interventions on behalf of their children even when they are sensitive about discussions of family life directed at them. To criticize family structures is to attack a person’s core identity, which understandably does not promote collaboration.

Being Local: Having the school close by was an important factor for Whitley residents. The deep local roots of Whitley are reflected in the number of mentions of children attending the same school as their parents. Although the quality of schools is valued, there was little evidence that parents had a resentful attitude about the school their children attended, even when that school had not been selected by choice.

Parental Aspirations: Opportunities and Challenges

No lack of aspiration: In keeping with research carried out elsewhere3, it was clear that there is no lack of aspiration amongst ‘disadvantaged children’, but there is a lack of know how in terms of how to sustain and achieve those aspirations. Parents simply do not know the pathways. The information provided by schools is therefore very important, but schools may need to work harder to get it across. Live examples (contact with someone from the same background who has taken the path aspired to) has been found to be more useful in helping young people take the path themselves than long explanations of advantages and disadvantages4.

Importance of school clubs: Children who attended school clubs tended to be happier at school and more likely to aspire to higher education. Part of this may be parental influence (engaged and aspirational parents were more likely to send their child to a club) but even controlling for multiple elements of parental influence, there was still evidence of a significant link between attendance of a school club and being happier and wanting higher education.

Happiness at school: When asked directly, parents felt that their child’s happiness at school depended on ‘managing well with lessons’, ‘having good peer friendships’ and ‘having encouraging teachers’. Whilst other data backs this up, it was also found that happiness is correlated to behaviour in school and to parental influences. Parents felt that their children were held back by lack of confidence, lack of money (goes with lack of opportunity), and the need for their child to ‘knuckle down to work at school’. Very few blamed teachers or negative family circumstances.

Barriers to aspiration: As for behaviour, money barriers, barriers in terms of ability and having special needs were all linked to misbehaviour. Perhaps our system favours the wealthy, the able and the socially dextrous, and those less favoured in these areas resist conforming to it. Parents who had had a bad experience of school themselves were not more likely to have children who got into trouble at school, although some other indicators of parental circumstances were linked to child behaviour.

Parents and schools together: Parents felt that communication with schools can be difficult when parents (and their children)

do not feel informed/do not understand; feel threatened; feel that bullying/issues with other children are not being dealt with; feel that they are only ever contacted when something is wrong and not when their child is doing well and working hard. Some parents were aware that they only make things worse by refusing to cooperate or by spreading bad reports about the school. Reflection on the issues that can be improved, and especially noting the points of tension between parents, teachers and young people that might be eased can be helpful.

The last point about working together is summed up by one of our Whitley Researchers below:

‘We Need to Work Together’

I am a Whitley Researcher and the following is a small contribution to the report’s conclusions. I carried out many interviews and questionnaires with parents about their relationships with schools and their hopes and aspiration for their children.My Main Findings:

Unfortunately many of the parents I spoke to (mostly Mums) felt quite negatively about their relationship with their child’s school. This was for a variety of reasons such as, the school not being that friendly, previous experiences and a fear of authority.However, stepping back from the research now I feel that this was also down to the parents themselves. Some parents brought with them a very negative view of school and education in general largely due to their own experiences and history. They brought this to their child’s situation and they had some inherent, embedded fears and concerns that actually could hinder their child’s progress.

Much work needs to be done in order for us as practitioners to get past this. We need to make school a positive place for our young people to grow, learn and explore the world!

One of the other issues that stood out to me was how very important transitions are!! All transitions - from Nursery to Reception to KS1 to KS2 and in particular Year 6 to Year 7. Many parents felt that these transitions were very important to them and their children, and that they could be managed better.

In my view these transitions should start earlier. Way before the end of Year 6 the children should be learning about, visiting and becoming part of Year 7. Particularly as very little learning takes place in Year 6 after SATS in May!

Another important idea to me as someone who works in a school, is that the Teachers of Year 6 and Year 7 need to communicate with each other more. Discussions need to happen about transition, expectations of learning and behaviour and for more visits to each other’s settings to occur. To observe the children in their previous and future schools may help the process.

FINALLY, on this matter in particular I feel very strongly that we should be in this together. We need to join up on this and not treat transitions as separate entities! To make them more successful we need more unity.

BOX 5.1 PARENTS – SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

Feeling that school staff are welcoming and approachable was very closely correlated to parent engagement with the school and support of the school. 84% of parents rated most school staff as being welcoming and approachable.

Although Whitley’s primary schools were seen to have a better reputation than secondary schools, most parents were positive about their own child’s school. Having the school ‘local’ is important to Whitley residents, who have often been around since generations. Happy parents are associated with happy children.

Three key issues damage parental communication with the school and affect their positivity:

- A lack of mutual respect (parents for the school and the school for parents); Parents know they influence child outcomes. However, parents resist the idea that their circumstances hold their child back. Parents of all backgrounds want their child to do well. Feeling judged puts parents on the defensive, damaging communication with the school.

- Feeling the school is not addressing parental concerns, especially bullying concerns.

- Not understanding/feeling informed. More information was wanted. Also positive news – not only being contacted for negative reasons. Emailed communications were seen as useful. Letters home are still the most effective form of communication. However, the school communicates in multiple ways and picking up on multiple channels was correlated to better engagement with the school. Highly engaged parents felt that appropriate homework is an important tool for increasing engagement still further. Many parents (esp. those with their first child) had not picked up on existing channels of information however and did not understand how things work at school. Also timelier reminders would help working parents plan their time. Having more information about what their child is doing helps parents to support their child’s education.

Regarding child happiness at school, managing well with lessons, having good peer friendships and having encouraging teachers were seen by parents to be the key factors. Good behaviour and parental influence was also correlated to happier children.

Although peers were partly blamed, most parents felt their children to be responsible for their own behaviour. A small role was also attributed to lack of understanding. Correlations within the data suggested that misbehaviour was also linked to money barriers, barriers in terms of ability and having special needs (in other words, those feeling disadvantaged were less inclined to cooperate).

Lack of confidence, lack of money (which goes with lack of opportunity) and the need for a good attitude to work were seen by parents to be key barriers to child aspiration. Few parents blamed teachers or negative family circumstances, although both of these factors were also associated with aspiration.

Almost half of parents (particularly those in difficult circumstances) wanted the school to help provide life-skills. There is no lack of aspiration, but there is a lack of knowhow in terms of how to achieve those aspirations. Parents tended to think more children wanted higher education than the young people themselves expressed. The message about the benefits of higher education or other forms of training is not reaching young people.

Better off children went to extra-curricular clubs (and the clubs may also contribute to them being better off).

In the following chapter, we move on to explore teachers’ views on young people’s life chances in South Reading and on the role played by school-parent relationships.

1Sanders, M. & Groot, B. (2018) Why text. The Behavioural Insights Team. [online] http://www.behaviouralinsights.co.uk/trial-design/why-text/

2Also in the Scottish study, the desire for teachers to teach life-skills was found to be almost twice as prevalent amongst people who have no qualifications themselves. Bradshaw, P., Hall, J., Hill, T., Mabelis, J., and Philo, D. (2012). Growing Up in Scotland: Early experiences of Primary School, Edinburgh: Scottish Government. [online] http:// www.gov.scot/Publications/2012/05/7940/13

3Menzies, L (2013) Educational aspirations: how English schools can work with parents to keep them on track. Joseph Rowntree Foundation. [online] https://www. jrf.org.uk/sites/default/files/jrf/migrated/files/england-education-aspirations- summary.pdf

4Soon, Z., Chande, R. and Hume, S. (2017) Helping everyone reach their potential: new education results Behavioural Insights Team [online] http://www. behaviouralinsights.co.uk/education-and-skills/helping-everyone-reach-their- potential-new-education-results/