6.1 Introduction

The Whitley Researchers felt it was important to explore teacher views on school-parent relationships, barriers to child development in Whitley and how these could be overcome. Because parents, teachers and teenagers had all been asked similar questions, we could also see which issues were understood in a similar way by all parties, and where the differences of opinions lay.

This chapter also includes data from the snapshot interviews undertaken by the Young Whitley Researchers with 15 JMA teachers about their own past and present aspirations, what influenced them, the helps and hindrances they encountered and their views of student aspirations.

6.2 Teachers: Youth Aspirations and School-Parent Relationships

In total, 38 school staff members completed questionnaires1. Just over half of the respondents were teachers in a secondary school (JMA), and the rest, teachers in primary schools. The respondents were all women in primary schools, and about half were women in secondary schools. The majority of the respondents were regular teachers, although teachers with special responsibilities (like Head of Year or Head of Department) were very well represented (just over a quarter of all respondents). Two teaching assistants, an office staff member and an area officer of SEN and inclusion also responded.

Teacher motivation and challenges

Teachers were asked about the most rewarding part of their jobs. Most of them were motivated by their love of seeing children learn, develop and achieve as they experience education. They were rewarded by the ‘light bulb’ moments and they reported how much they enjoy seeing the children happy. Many mentioned their enjoyment of interacting with children, and the opportunity they have to ‘make a difference’. Having enthusiastic children was seen to be highly rewarding, but so was seeing a child progress and change after a struggle.

Likewise teachers were asked about the most challenging or least favourite part of their job. The number one most challenging issues were found to be:

- Behaviour (mentioned by 46% of staff, but primary and secondary school teachers to the same degree).

- Paperwork and to a lesser extent, marking (mentioned by 29%, and especially by primary school teachers).

Some teachers mentioned feeling distressed by the traumatic situations some children face, which they are helpless to address within the classroom, and three teachers mentioned the challenges of dealing with unreasonable or unsupportive parents. As one of our Whitley Researchers commented in Box 6.1:

Box 6.1: Teaching Pressures

I just wanted to say as a Whitley Researcher my main findings from the questionnaires were that although, every effort by school /teachers is made to inform parent and carers not all of the information is acknowledged or received well. I work in a school and feel both parties must take some responsibility for this. There is a lot of pressure on all teaching staff to improve standards, with some reluctant students at times, and this drains both resources and people power, although the attainment still needs to be met. The staff I work with work extremely hard during the working day and behind the scenes to ensure all pupils enjoy their learning.

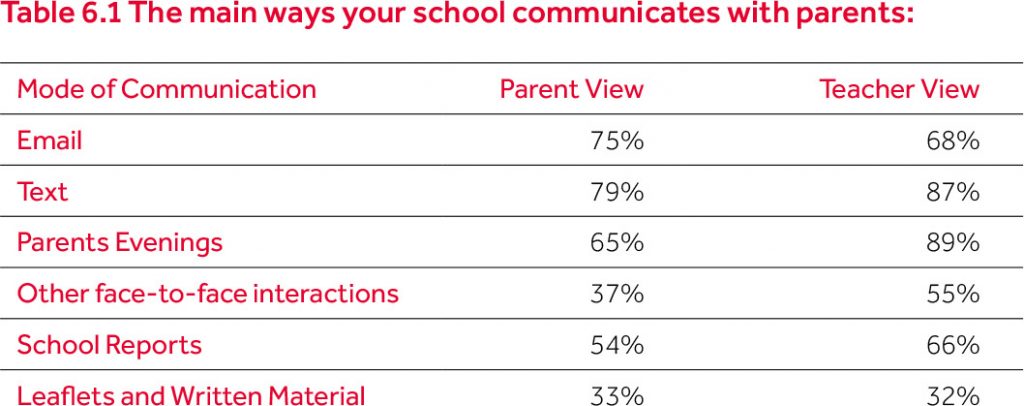

Communications between school staff and parents

Parents’ evenings are the mode of communication most cited by teachers, with almost all teachers mentioning it. Far more teachers mention this (and other direct and personal forms of interaction) than parents do – only two thirds of parents mentioned parents’ evenings as being a main way of communication for example. This highlights the known problem of some parents being out of the loop, and particularly when it comes to face-to-face contact.

The reports of parents and teachers on modes of communication are broadly similar, although teachers tended to be more aware of multiple forms of communication than parents were. If anything, teachers underestimate the importance of email. One teacher said ‘read receipts’ would be helpful, but it would seem that more parents pick up on emails than teachers think. Getting emails do not make any difference to how well-informed parents feel however – the parents’ survey revealed that only letters (the least-used mode of communication) were associated with parents feeling better informed.

According to teacher responses, primary schools do more face-to- face interaction outside of parents’ evenings. Secondary schools rely more on websites for communication. Although teachers are equally likely to cite school reports in primary and secondary schools, parents are more likely to pick up on these in secondary schools (parents were significantly more likely to mention school reports as a way of communication when their children were in secondary school as opposed to primary school).

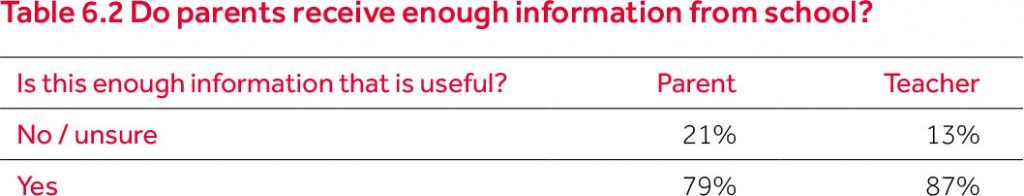

Regarding whether teachers feel this information is sufficient and useful (easy to understand and act upon), their impressions were slightly (but not significantly) more optimistic than those of parents (see Table 6.2). Since parents not happy with communications were mostly (not exclusively) those not accessing the information available, this is a reasonable finding.

Of the few teachers who felt that communications were insufficient, there were mentions of the problem of some parents not accessing the information that is available. Also, the mention to be timelier with reminders, which was a point brought up by parents. Apart from maybe providing materials for the parents who want extra involvement in their child’s education, this suggests that teachers have a good understanding of where communication works and where it does not.

We asked teachers what are the most common issues or questions that parents raise with the school or about their children. Teachers, both in primary and secondary schools, said that the most common issue was the behaviour and attendance of the child ( just over half of the teachers mentioned this). Parents also want to know about their child’s progress in class, child-teacher relations, peer relations and wellbeing generally.

A quarter of teachers mentioned parents bringing up the topic of disputes with other children and/or bullying concerns (this was particularly in primary schools). Around a third of teachers say that they are also asked for information about school events, class or lunch arrangements and so on. Finally, there were homework related questions, more often asked of secondary school teachers.

It is interesting that child behaviour, clearly a sensitive topic, is one of the foremost issues under discussion with parents. Managing poor behaviour is also cited by teachers as one of the most challenging/least favourite parts of their job. The fact that so much conversation revolves around behaviour could be a factor in making parent-teacher relations tenser that the progress of the child actually warrants. Parents also mentioned how unfortunate it is that the most common communication with schools seemed to be of a negative kind.

Teachers went on to tell us what makes it easy and what makes it hard to work with parents on these issues or questions. The most common response (mentioned by over 80% of teachers) was to do with the way in which parents communicated. Teachers found it much harder to work things through where parents took an aggressive stance, resisting the school and its policies or setting their family up against the school instead of trying to support the school approach and work things through positively.

The second most frequently mentioned communication problem was where parents were simply disengaged with the school rather than reinforcing the learning.

Less frequently mentioned issues that made it hard to communicate included parents not understanding what is going on, or parents not following established procedures for sorting things out. Making the time to engage with parents was seen as important in working things through.

It is interesting that both teachers and parents emphasise this need for approachability and a willingness to listen when communicating. This is clearly something that cuts both ways.

Does the school do enough to support students?

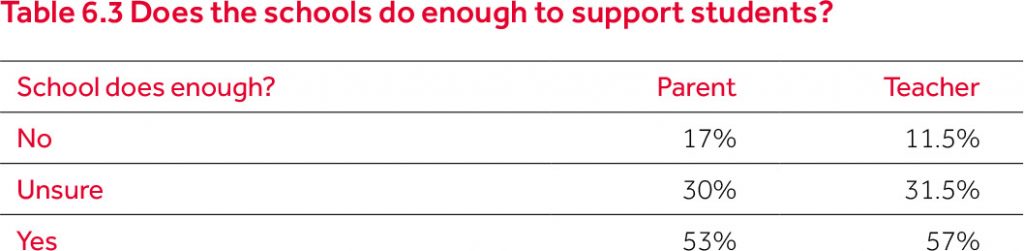

Teachers and parents responded in very similar ways to the question, “do you think the school does enough to prepare and inspire children for their next stage in life,” – there was no significant difference between responses.

Teachers in secondary schools were particularly concerned about preparing children for their next stage in life (although parents were equally worried in primary and secondary schools). These teachers felt that the education was not sufficiently holistic. Children were not learning to become independent. Life skills were lacking and they need better preparation. This is exactly the wish/concern expressed by parents who felt the school could do more too, even from primary school level, and especially amongst parents who themselves are struggling with difficult circumstances that make it hard for them to fulfil this role at home.

Child happiness

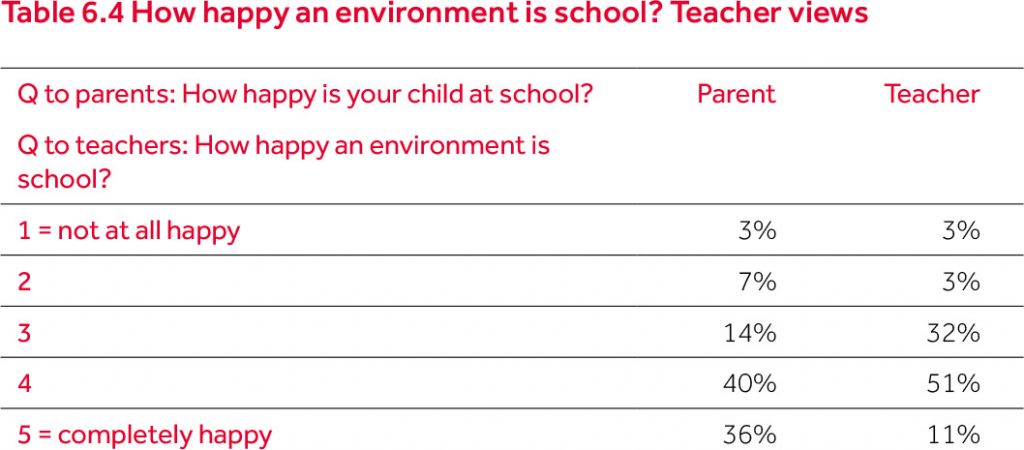

Parents tended to rate their own children happier in school than was the teachers’ assessment of the school in general (see Table 6.4).

Teachers were more likely to see primary schools as a happy environment, although parents were equally likely to say their children were happy at school in primary and in secondary. Male and female teachers rated the happiness of the (secondary) school in similar ways.

Teachers were asked what key factors influenced how happy children were at school. The top responses in order of priority were:

- Positive relations with peers (mentioned by nearly half of teachers).

- Positive relations with school staff.

- Managing well with the school structures and with lessons.

In these three, teachers’ responses closely resembled the responses of parents and the responses of young people themselves – it would seem that the factors affecting happiness are widely understood.

Just over a third of teachers mentioned how important it is for children to have support structures in place for the things that they struggle with. Some teachers also mentioned the link between reduced happiness and poor behaviour – the way the child engages with school structures is important to their wellbeing. Getting involved also with extra activities in the school was seen to go with happy children (a suggestion borne out in the parent survey correlations).

Just under a third of teachers also mentioned home influences on the happiness of children at school (even coming to school hungry). Again, this was borne out in the parent survey correlations, and is a point that is returned to in later questions.

Child behaviour and improving child support

Child behaviour is an important question since dealing with misbehaviour is a challenging and unpleasant part of a teacher’s job. Some of this was low-level disturbance going on and on, but some was related to highly confrontational pupils.

When asked what are the contributing factors to child misbehaviour, teachers cite three major factors:

- The first is peer conflict or acting up for peers (mentioned by nearly half the teachers).

- The second concerns home issues (stress, lack of support, poor diet) along with personal immaturity in communication and in coping with school demands. Children with special needs were mentioned as finding it especially hard to cope with school demands.

- The third, mentioned by 36% teachers, has to do with teacher skill and the setting of inappropriate work demands.

These three factors overlap with the three reasons put forward by parents. Peer influence is the same. Child lapse of judgement is similar (although teachers put more emphasis on home influences here than parents do. Certainly correlations in the data confirmed that misbehaviour was linked to families facing money barriers). Poor teacher management is also similar, although significantly less parents mentioned this compared to teachers, who are much harder on themselves than parents are on them.

Teachers were asked what would help most in dealing with these difficulties. Some said that experienced and understanding teachers, along with clear, consistently applied boundaries were important. Teaching assistants are valued.

However, it emerged that big issues are faced that cannot be sorted out within the classroom, however good the teachers. Lack of time, resources, or capacity to deal with such issues (some of them very distressing) is a problem. Time outside of the classroom to work these things through, pulling in the collaboration of parents where possible, and accessing specialist help where needed from child therapy specialists or social workers was very widely requested. Good communication is necessary to make this work, but this also takes time. It involves having space in school for things besides direct teaching but which aid the development of the child.

Some teachers felt that for children disengaged with learning, the curriculum was inappropriate and more focus on life skills would help, including working through peer relationship issues with young people. They mentioned how important it is to set the right kind of work for these students.

This brings us on to the issue of improving support for children. Teachers were asked not only what could be done better in school, but also what parents and authorities could do better to support their children.

Teacher views on how parents could improve their support

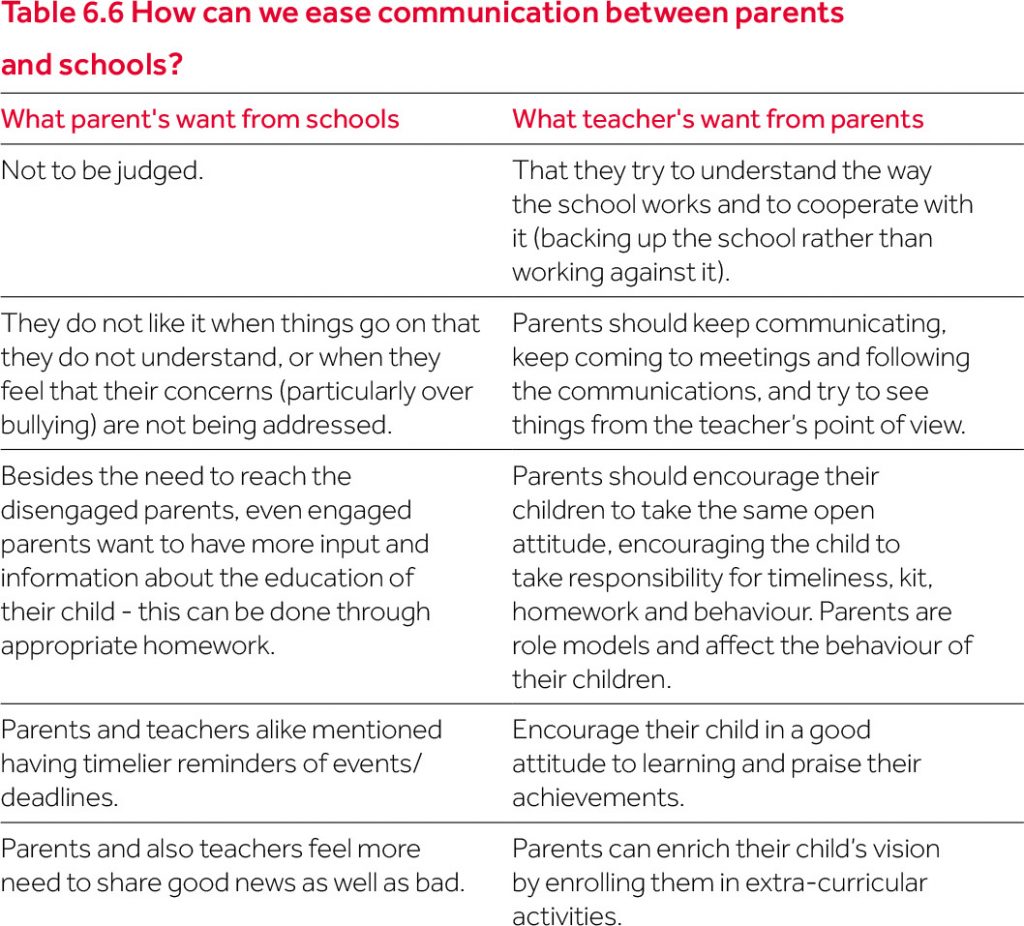

The number one advice of teachers to parents wanting to support their children in school was to:

- Try to understand the way the school works so as to cooperate with it.

- Keep communicating.

- Come to meetings.

Most other points flow from this:

- Ensure child attendance and timeliness, encourage responsibility for kit and behaviour.

- Encourage the child in their attitude to learning, ensuring homework is done and praising achievements.

- Back-up the school line rather than working against it. Realise teachers are trying to do the best for the child too, so they do not need to ‘defend’ their child from the school.

A few teachers mentioned other points about parenting such as limiting ‘screen time’ or letting the school know about issues at home that may affect the behaviour of the child.

Teacher views of how education authorities could improve their support

Regarding education authorities, some teachers asked for less emphasis on comparing final grades and more on the underlying factors (such as revision and homework!). In other words, they do not like the implication that they are responsible for everything to do with the success of the child when the playing field is not level to start with. They want more listening to where the real issues are locally and the direction of efforts into dealing with those.

A few teachers suggest more training, also for parents. They also suggested more funding for social care and vulnerable families, and more funding for special needs pupils. There needs to be more support and funding to enable the school to attend to pupils with behaviour problems – addressing these needs outside of regular classes. This involves funding for outside agencies that are involved with these things as well as funding for more school staff, such that staff are not only teaching, they also have the time to deal with issues that go beyond teaching.

How bright is the future?

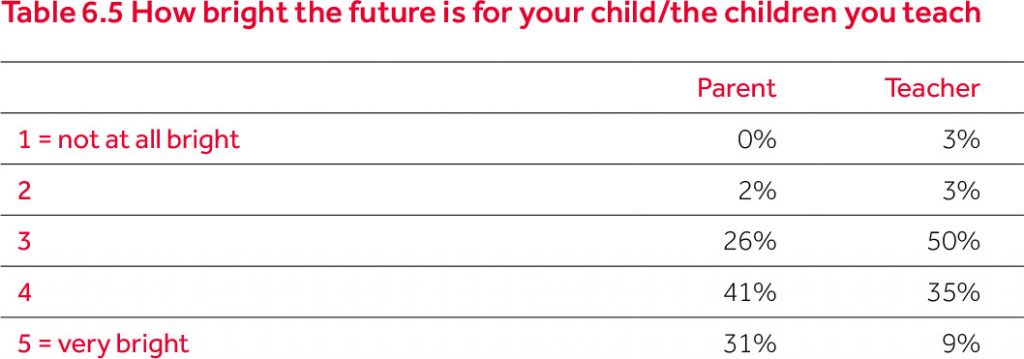

Parents reported slightly brighter futures for their children than teachers. Most teachers think that the future is at least bright for their pupils but they tend to be more uncertain about the future than parents or young people.

It must be noted that these results are not directly comparable. Parents are being asked about their own child for whom they may give a biased answer, whilst teachers are asked about Whitley children in general. However, this does challenge the view that Whitley parents have low aspirations for their children. When talking about ‘aspirations,’ there is a need to define the aims more clearly and the means of getting there.

Perhaps the pathways involve a positive attitude to learning, respectful behaviour, and overcoming barriers in terms of money constraints and low self-confidence. (Regarding self-confidence however, it was noted in the parent survey that it was the children who never got into trouble who were more likely to suffer from low confidence, which raises some interesting questions in itself).

Being prepared in these non-academic life skills is what parents felt held their children back as well. Secondary school teachers were especially worried about children getting adequate (non- academic) preparation for their future, and this lack of preparation had a big influence on the prospects they predicted for children. Thus, secondary school teachers were fairly pessimistic about the prospects of children in their school.

Teachers were asked what things favour the future of children who go to their school, and what things hold them back.

64% mentioned negative parental influence as holding children back

Regarding things that hold children back, the most frequently mentioned point (mentioned by 64% of teachers) was negative parental influence. Chaotic homes and generational poverty was seen to disadvantage children. Disengaged parents were seen to result in lack of good advice, direction, aspiration, and home support for the child. Internet influences, poor diet and too much ‘screen time’ were also mentioned as contributing negatively. Likewise, some teachers mentioned community influence, pressures and stigma. Some said there are a lack of role models with whom the pupils can relate.

It would seem that parents have a warmer attitude towards teachers than teachers have for parents. Parents and young people resisted the idea that their background held them back (even though they readily recognize that they bear responsibility for how things turn out). They defend themselves against being ‘judged’. The feeling of not being held back is positive, so long as resistance to criticism does not stop parents from being open to change.

As came out clearly in the parent survey, the process of teachers working these things through with parents is a delicate matter requiring good soft skills.

Other teachers remarked that children were held back by confused policies from the top and lack of resources, especially for more staff. Again it was suggested that children who cannot engage with the subjects might do better with an alternative curriculum and with a focus on the acquisition of life skills. Counselling/pastoral services are important.

As things are, negative home influences and limited school focus can lead to a poor attitude to learning, low expectations of self, a poor grasp on ‘life-skills’ and poor behaviour, all of which hold children back.

Regarding things that help children and young people forward in Whitley, teachers mentioned:

- Activities that widen the vision and enrich lives (some of them extra-curricular).

- A positive attitude to learning and to challenge.

- A positive ethos in schools, including inclusive school policies. • Good, encouraging teachers.

- Positive parental input.

1Our questionnaire was distributed through the WEC in March 2018. We do not suggest that our sample and data are representative of all teachers in South Reading.

6.3 Conclusions

In the conclusions, we compare the views of teachers with the responses of parents and young people to see whether there are key differences that might be focus for change:

The future’s not so bright. Teachers are more uncertain about the future than parents or young people. It may be that teachers have a better grasp of the difficulties facing the next generation in terms of jobs, rising housing costs and government cut backs.

Adequately Preparing Young People in School: Teachers, parents and children felt that futures were being adequately prepared for in school were all more likely to rate the future of their children more highly. Around half of teachers did not feel young people were being adequately prepared in these ways.

‘Adequate preparation’ includes a focus on helping students’ access pathways to:

- Enhanced attitudes to learning.

- Understanding the opportunities offered by higher education (and how to access it).

- Training in life skills and working around barriers that parents feel hold their children back (lack of money, opportunity and confidence).

- Disengaged children may benefit from a curriculum more relevant to their needs.

Child Happiness. We note that parents rate their children as being happier in school than teachers do, and they are also less likely than teachers to blame the school for the misbehaviour of their children. The vast majority of parents’ rate teachers highly on a scale of how welcoming and approachable they are. Teachers may therefore be encouraged – parents have a better opinion of their work than they might think!

It is unfortunate that most contact takes place where things go wrong (a low-point noted by both parents and teachers), which means that teacher-parent communications can seem more negative than they actually are. Both parents and teachers would like to see a higher number of positive communications being sent out so as to shift this balance.

Relationships and soft skills are important. Parents feel better when teachers are welcoming and approachable, and teachers also feel better when parents are cooperative rather than aggressive or unwilling to listen. Just as teachers need to avoid a judgemental attitude, recognising that parents genuinely care for the welfare of their children, so parents need to recognize that teachers thrive on seeing the children in their care happy and developing well; this is a strong motivating force for most teachers. Since both parents and teachers want the best for the child, there is a good basis for working together. Parents do not need to ’fight’ on behalf of their child. Parents taking a resistant or unsupportive attitude to the school was the top issue mentioned by teachers in making it harder to get things sorted out. Teachers also found it hard to work things through with parents who were disengaged altogether.

Child behaviour (or misbehaviour) is one of the most frequent issues parents bring up, as well as being one of the most challenging issues for teaching staff to deal with. Both parents and teachers clearly recognise the importance of good behaviour for child progress in school. No unexpected motivators for poor behaviour were unearthed – teachers are aware of the underlying factors and place higher expectations on themselves to help ease the way than parents tended to place on teachers. Teachers are also perceptive as to the other influences on child wellbeing at school (positive relations with peers and with school staff, positive engagement with the work, and getting enough support from home).

Support for Teachers. Teachers emphasise that time is needed outside of regular classes but still in school time to deal with behaviour issues, relationships issues and with other child development programmes. They want to pull in assistance from the local community and outside agencies – charities and specialist workers, working with parents where possible as well as with the children. Time and resources will need to be specially directed into these things. Teaching is one role of the school but in increasing measure (and especially in locations where families are unable to provide support at home) school staff believe that children (and even their parents) have need of support beyond their academic studies. Staff and resources need to be found to meet these needs as well. Disengaged children in particular should be given a curriculum more relevant to their needs, such as focusing on life skills.

Only just over half of parents and teachers feel that school preparation for future life is fine as it is. Both parents and teachers want more focus on teaching life skills to children who lack them. They both see the need to have additional training for children in positive modes of behaviour where necessary.

Nearly all teachers say face-to-face meetings with parents (for example on parents’ evenings) is a major channel of communication, but only two thirds of parents mention this as a main mode of communication. This suggests that at least one third of parents are not getting what is on offer. Teachers are aware that not all parents pick up on the forms of communication available to them. Conversely, teachers reach more parents than they think they do with email. Not that this necessarily helps parents to feel connected. Letters (the least used mode of communication) are important for this, as is parents accessing multiple forms of communication. In secondary school, parents rely less on informal face-to-face meetings to communicate, and more on school reports and the school website.

When asked to think about easing communication, here are the key messages that parents and teachers would like to tell each other:

We conclude with a snapshot on what the Young Researchers found when they interviewed 15 teachers at JMA in November 2017.

Box 6.2: Snapshot Interviews by the Young Researchers at JMA

15 teachers answered a series of questions asked by Whitely Young Researchers about their own past and present aspirations, about what influenced them, about helps and hindrances to their aspirations and about their view of JMA student aspirations. The interview questions were put together and carried out entirely by the Young Whitley Researchers.

It was interesting to discover that very few teachers set out to be teachers as a child, demonstrating how aspirations change over time. The influence of other people was the most significant factor in shaping aspirations – families in first place, but also teachers and role models. Life’s experiences and personal skills or inclinations played a part as well, with a few chance events thrown in. A desire to help others was mentioned several times as shaping the choice regarding becoming a teacher.

The current aspirations of teachers tended to be more quality- of-life focused than career choice oriented. Several teachers mentioned new hobbies they wanted to try or experiences they wanted to have, or the way they wanted to improve in their job, or their aspirations for their own children.

Obstacles to their own aspirations mentioned by teachers included lack of confidence, life’s set-backs, personal failings and lack of support. Things that aided teachers in their achievements included family and friends and also internal motivation – you have to help yourself!

Finally, teachers were asked whether they thought students at JMA had any aspirations. The answer was a qualified yes. Most teachers added the need for the right support, especially to express aspirations and to explore new possibilities. Students could think bigger, but then they need to act for themselves on what they aim for. The need to take responsibility for one’s own future came out clearly, both in the teacher’s reflections on their own life, and also in their advice to JMA students.

BOX 6.3 SCHOOL AND TEACHER’S – SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

Managing child behaviour was one of the most challenging issues. Teachers were well aware of all contributing factors to misbehaviour, and they expected a lot of themselves too.

Teachers wanted time and resources outside of regular classes to deal with behaviour issues, relationship issues and for other child development programmes, assisted also by outside agencies.

Aspirations change over time. Although shaped by families, role models, life experiences, personal inclination, timely information and support, teachers also emphasise the need for young people to take responsibility and take action in order to secure their own future.