Research Aims

This study explores the aspirations of young people in the Whitley community and considers the barriers they face. It also investigates how schools, families and the wider community can better collaborate in order to help their young people realise their aspirations.

Low aspirations among young people and their families in disadvantaged areas, is often seen at policy level as explaining their failure to do better at tests of attainment including access to further and higher education. Is Whitley a community characterised by a lack of aspiration and to what extent can improved relations between families, schools and communities make a difference? This research set out to respond to these questions.

Background

Reading Borough Council’s Housing Services commissioned the research from its Decent Neighbourhood Fund, with the University of Reading. The proposed research project was backed by the Whitley for Real (W4R) partnership – a collaborative group of local service agencies and community groups aiming to strengthen the ‘local voice’.

Following an extensive consultation and planning phase led by the Whitley for Real partnership the research commenced in May 2017.

Whitley

The ‘Whitley community’ is defined here as the two wards of Whitley and Church and adjoining areas of Redlands and Katesgrove wards. Whitley and Church wards are the most deprived in Reading. In total both wards contain two areas in the 10% most deprived on the overall index and three areas in the 5% most deprived on the ‘education, skills and training index’ (five Lower Super Output Areas as recorded by the Office for National Statistics Indices of Deprivation).

Ethos

This research initiative reflects a close partnership between the University of Reading and the Whitley Community Development Association’s (WCDA) Whitley Researchers. Past collaborations have resulted in a range of research publications including the ‘Working Better with Whitley’ transport survey (2015). The partnership working was extended in this project to include students at the John Madejski Academy – the Young Researchers.

The ethos is one of engagement and participation – communities are encouraged to get involved in conducting their own research. The belief is that communities should devise their own solutions

to local issues – locating knowledge generation at grassroots level. Top down surveys often miss the more relevant issues that impact on local residents and fail to recognise the tacit understandings that residents have of their own neighbourhoods. ‘What we know is the starting point for what we do’.

Method

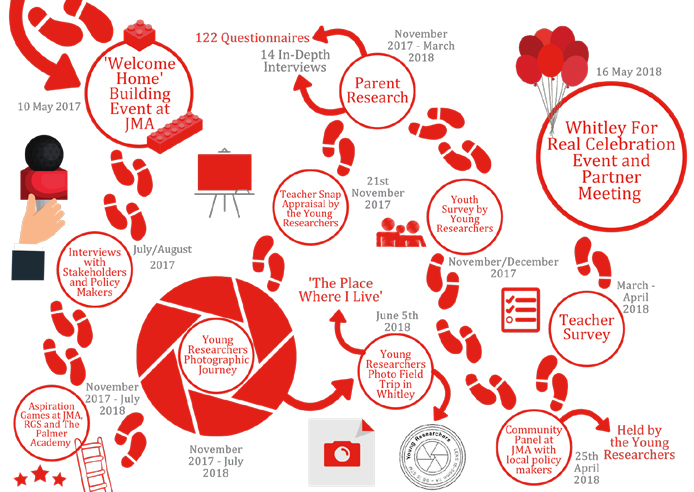

A participatory method was adopted to explore issues around youth aspirations, school-parent relationships and transitions to higher education, training and work. The Whitley Researchers approach places great emphasis on the research journey or process – as important as the knowledge gathered.

We co-produced our methodology with participants, partners and stakeholders over a sustained preparatory period, involving regular meetings of the W4R Steering Group chaired by Reading Borough Council’s Chris Bloomfield and Jill Marston. Our most exciting initiative has been the development of an award winning ‘young Whitley Researchers’ team at John Madejski Academy (JMA) who have created their own methods, including an ‘aspiration game’, to explore issues around aspirations and future lives with their peers.

What followed was a multi-method research journey with several strands of activity and investigation shown in the Figure below – a co-produced qualitative research programme that explored the attitudes and experiences held by young people, parents and schools and also the wider community. The unifying theme was aspiration in Whitley and local co-operation for advancement.

Key conclusions and recommendations

This section presents conclusions and recommendations in the same frame as the full research report: youth aspirations, Whitley parents, teacher’s views and community opinions. Overall, however the assumption is that the recommendations are supportive of cross-sectional co-operation.

Youth aspirations

Conclusions here included the following:

- There is no shortage of aspiration among young people in Whitley. The aspirations change over time from younger dreams to more mature goals as students move through the school grades. Greater support is needed to navigate and sustain the aspirational journey.

- Young people want to find their own voice and place. They want two-way relationships with adults and help in finding their voice and guidance from a range of sources to make their voices heard and to be listened to.

- Effective family and friendship networks are central to happiness and well-being – it is important to have people who believe in you and have your best interests at heart. There is perception among young people that not enough is being done about bullying and they loathe injustice.

- Students who struggled with the school work and students who felt that the school could do more to equip them for the future were less happy. Good relations with peers and teachers also had a significant impact on happiness.

Recommendations include:

- Schools with additional community assistance should hold regular reviews and evaluations of student’s future hopes or intentions. This could include a systematic approach to career guidance and work experience with informed knowledge of the local labour market and use of role models. Attention should also be directed at the minority of students who are alienated from school purpose or personal direction.

- A more democratic practice should be considered in schools but also for young people in community settings. Youth voices could be heard in a variety of locations in and out of school – perhaps in the form of community panels around local issues. Schools could explore more interactive sessions with young people focused on more listening and a questioning approach.

- There should be a more informed and supportive approach between young people and their teachers (and parents) to help deal with anxiety and trauma and exam or test pressure. Access to support groups and outside help – such as Reading’s proposals for a ‘Trauma Informed Community' – could be explored. The aim is to enhance young people’s happiness.

- Curriculum enrichment including more clubs, experiential learning outside school, joining in addressing community issues e.g. around mental health and engaging in creative and innovative ways of learning, could all help reduce issues or concerns around school work. Parents too could be invited to collaborate in these provisions.borate in these provisions.

Whitley parents

Conclusions include:

- Parents were aspirational for themselves and their children. However, parents own poor personal experiences of school were linked to fewer aspirations for their children to go on to higher education and they were less likely to engage in school activities or events such as school clubs. Overall, parents still hoped for good outcomes for their child regardless of past school experiences.

- Parent perceptions of school staff approachability is the most significant factor that shapes parent’s optimism about their child’s future and aspiration for their child to go on to higher education. Most parents felt that school staff are welcoming and approachable at primary and secondary level.

- When asked directly, parents felt that their child’s happiness at school depended on managing well with lessons, having good peer friendships and having encouraging teachers. Additionally, happiness is associated with behaviour and parental influences. Parents felt that their children were held back by lack of confidence, lack of money (goes with lack of opportunity) and the need for the child to ‘knuckle down to school work’ – very few blamed teachers or negative family circumstances.

- Communication between parents and schools is influential in matters such as parental engagement in school events and satisfaction with their school. Parents who felt well-informed by the school were more likely to report their child as happy in the school. Text was the most cited mode of communication yet letters to parents may not have had their day.

Recommendations include:

- Parents should be encouraged and supported to understand the way their school works and to co-operate with it – backing up the school rather than working against it. Keeping up with communications, attending school meetings and in particular talking positively about the school. This latter factor affects their child’s attitude and also the child’s long term aspirations. Joint parent/teacher groups could model new co-operative relationships.

- Establishing a community wide parents learning group run by parents in partnership with New Directions could assist parents in understanding how and what their children learn. This should not be thought of as a parenting strategy but as a means to developing with parents a sense of agency for their own learning and aspirations and a wider understanding of how school systems work locally. Knowledge of opportunities and the local labour market may also help parent’s aspirations.

- Parents might also be encouraged to have a more engaged role in their school – partly to encourage a new understanding of school as a collaborator in their child’s future and well-being and partly as a location where the schools assets and resources are also the parents or communities. Examples include adult education or training classes, running school clubs, joining in experiential learning such as local history, organising work based visits or supporting school councils or community panels with the students.

Teacher’s views

Conclusions:

- Our research found out that secondary school teachers are less certain than parents about whether the future is bright for Whitley youngsters. Teachers have perhaps a better grasp of the difficulties facing the next generation in terms of jobs, rising housing costs and government cutbacks.

- Key factors teachers mentioned influencing children’s happiness at school included positive relationship with peers, positive relations with school staff and children managing well with school structures and with lessons; responses closely matching those of parents. A third of teachers also mentioned home influences on the happiness of children at school – even coming to school hungry.

- Teachers said that the most common issue that parents raised with them was the behaviour and attendance of the child – including disputes with other children and/or bullying concerns (particularly in primary schools). For most teachers managing poor behaviour was one of the most challenging or least favourite parts of their job. Because parent-teacher communication often revolves around child behaviour, tensions in communication may be unnecessarily high.

- Asked what hinders their school’s children, teachers referred

to negative parental influences including chaotic homes or disengaged parents but also external factors such as confused policies from the top and lack of resources. Help factors included activities that widened the vision and enrich lives (some extra- curricular), a positive attitude to learning and to challenge, good encouraging teachers and positive parental input.

Recommendations:

- Adequately preparing young people in school should include helping student’s access pathways to understanding the opportunities offered by higher education and how to access it, improving attitudes to learning, providing curriculum enrichment relevant to children’s interests, aspirations and needs and training in life skills. There should be a focus on the barriers that parents feel hold their children back such as lack of confidence and lack of money.

- Teachers might review their ‘approachability’ – how welcoming is the school and how respectful is it towards parents. Parents are more positive about teachers than teachers are about parents – nevertheless, parents should be encouraged not to fight on behalf of their child. Teachers and parents are on the same side. Measures such as letting parents know more effectively what

is going on, giving communications a more positive tone and providing more space to enable parents and teachers to talk to each other – even informally e.g. meals together for parents and teachers. - Explore and implement clear pathways to a brighter future – focusing on the value of work experience, the local labour market opportunities and having the ‘right’ attitude. Parents, teachers and students need to work together to provide sufficient preparation for the future.

- Support for teachers is vital – teachers emphasise that time is needed outside of regular classes but in school time to deal with behaviour issues and with other development programmes. Pulling in assistance from the local community and outside agencies such as charities and specialist workers could assist both teachers and parents with their children. Time and resources will need to be specially directed at these priorities.

Community

Conclusions include:

- Whitley is a community showing stark levels of disadvantage and inequality when compared with other Reading communities and low achievement in education and skills against national measures of deprivation. In spite of or because of this it also demonstrates a strong community spirit and a willingness to tackle local issues together.

- The quality of relationships across the community is often based on lack of trust and respect. There are divisions and tensions between residents/parents and local institutions and service agencies - reflected in residents suspicions about the attitudes and assumptions that these agencies manifest; some residents feel patronised and looked down on.

- For young people particularly there is a severe lack of services and activities that – if available – could play a key role in encouraging and supporting confidence, skills and attitudes that assist in sustaining aspiration.

Recommendations:

- • Through the leadership of Whitley’s most active and influential agencies there should be a co-ordinated effort to establish an inclusive community aspiration - one that reflects a shared hope and practices for the future of Whitley. It could take the form of a ‘big umbrella’ under which the community widely can agree on common values for a strong aspirational movement.

- An audit or register of local capabilities and physical assets might encourage a more positive view of the Whitley neighbourhood. Whitley has a lot to offer but lacks the knowledge of what is available; it has resources that could be marshalled for wider benefit, for instance for schools and parents. An exploration of further resources to attract should also be a priority.

- The need for more collaboration and improved relationships could be addressed via communities of practice and provision of art of conversation events. The former envisages a cross sector project bringing university, community and schools together in a joint exploration of a pressing local issue such as mental health. The latter is a series of specific events bringing together disparate groups of residents and workers in Whitley to tackle issues of respect and trust together.

- The presentation of findings in youth, parent, teacher and community headings in this research offers an opportunity to set up each as the writers of a handbook for their sector presented as a guidebook or a manual to encourage new attitudes, practices or support.

Moving Forward

The breadth and richness of this research has produced an abundance of findings and conclusions that prompt a wealth of recommendations. Underpinning the research method was an ethos of participatory engagement and community involvement and our proposal here is that the recommendations and their translation into action is equally participatory. Moving forward, the W4R Steering Group will transform into a W4R ‘Action Group’, augmented with new service providers, young people and their families, to help translate the findings and recommendations into co-produced task oriented plans. We suggest that young people themselves must be at the heart of designing and shaping the outcomes of future actions.